Prem Sahib (b. 1982, London). Recent exhibitions and performances include Alleus, co-commissioned by the Roberts Institute of Art and Somerset House Studios, at Somerset House and Edinburgh Art Festival (2024); The Life Cycle of a Flea, Phillida Reid, London (2023); and forms of the surrounding futures, the 12th Göteborg Biennial for Contemporary Art, curated by João Laia (2023). Sahib’s work has been shown widely institutionally, including solo exhibitions Balconies, Kunstverein Hamburg (2017) and Side On, ICA London (2015) as well in group shows at Sharjah Art Foundation, Sharjah, UAE; Migros Museum, Zürich, Switzerland; Whitechapel Gallery; Hayward Gallery, London; KW Institute of Art, Berlin, Germany; Des Moines Art Centre, Iowa, USA; and the Gwangju Biennale, South Korea.

Prem Sahib in conversation with Francesco Ventrella

Artist Prem Sahib discusses their exhibition Documents of a recent past at Studio Voltaire with art historian Francesco Ventrella.

Sahib’s work spans sculpture, installation, and architecture, often engaging with the aesthetics of minimalism to explore personal and political narratives. Their practice is deeply informed by the social dynamics of spaces—both public and private—where moments of connection, longing, and anonymity unfold.

In this discussion, Sahib and Ventrella reflect on the ways queer histories are embedded in materiality and form. They consider how Sahib’s work negotiates visibility and erasure, presence and absence, particularly within urban environments and spaces of social interaction.

Francesco Ventrella: Thank you. Thank you very much for hosting us. So we decided to introduce each other and let me see if I can do it from memory. So Prem is a multimedia artist and he works with sculpture in installational forms. Sculpture for Prem is also a way of thinking about politics, human relations, bodies and how bodies orient themselves in space and how this space becomes political. I have come across your work for the first time in 2015. This is the ICA and the title of the project was Side On and I didn't know you at the time and I fell in love with one piece in this site-specific project which is called Watch Queen, and it is this tall sculpture that overlooks this installation. So we will probably be on this side, I think, overlooking what is going on in the concord of the ICA. And yeah, I just, you know, I just fell in love with the title. I probably identified with the Watch Queen. I told you this before and so it really, really spoke to me. Prem has done a lot of exhibitions nationally and internationally, and you have also organised a project space at Ridley Road which closed down recently because the building is being redeveloped. And that is one of the things that comes across in your work a few times. And with George Henry Longley and Eddie Peake you organise a party, Anal House Meltdown, and I don't know when the next one is.

Prem Sahib: We’re doing a few abroad at the moment.

Francesco Ventrella: We met for the first time in 2019 and we've been friends since.

Prem Sahib: Thank you, Francesco. And thank you everyone for being here. I am going to look up my notes, I'm afraid, but I wanted to introduce you as Francesco Ventrella, who is a writer and academic that I've got to know over the years. And I often find myself chewing your ear off at inappropriate times, like on a night out. So I'm really happy that you accepted this invitation to speak more formally. But you also invited me to speak about my work at Sussex University, where you teach art history and your background, as I know from your bio is in cultural studies and the history of art, and your research is predominantly in feminist and queer interventions in art history and its institutions. I also read in your bio that your research includes the cultural field of affect, feelings and emotions, which is something that I'd love you to talk a bit more about today as well, because I find that fascinating. And also, you're involved in the Centre For Study Of Sexual Dissidence. You've written on gender, sexuality, resonance and the voice, which is why I thought it might be interesting for us to speak a bit today about how that relates to some of the work that I'm showing next door.

Francesco Ventrella: Yes, thank you. Maybe one way to start is to think about the fact, you know, this is a project about The Backstreet, which was a nightclub, a sex club in East London. I've never been to The Backstreet. And I remember when we first spoke about doing this conversation together, that's the first thing that I told you. But I've never been to The Backstreet, you know, I don't want to be an interloper. And then we started to think about the fact that an art project, you know, like the one that you see next door, obviously, speaks in a particular way to people who have been there and therefore can have a personal attachment to the place, but also it speaks to other people who have not been there. And I think the authenticity lies in the relations that different people can build with the project as it is next door. So the question, perhaps, is about how did you come across this project? How did you think about the fact that this was a space for a particular type of clientele, a particular type of queer man? And how did you think about turning it into a project that instead is open to the wider audience?

Prem Sahib: Yeah, thanks. I mean, in some ways, I've been making work about these types of spaces for quite some time. And at the sort of beginning of the presentation, my work at the ICA, I think here I was making a lot of work to do with a venue called Chariots, which was a gay sauna in East London. I was interested in transcribing my experience of that space into sculptural forms, maybe thinking about the different formal and material qualities and what they might hold, in terms of my experience of being there. So I was often using a lot of tiles, materials that can be wiped clean, things that related to ideas around hygiene and yeah, like this pedestal, for example, is something that I had measured in the darkroom of the club in, you know, I measured it as 11 hands by 10. And I liked how that became a way for me to transcribe it somehow, outside of the space. And then it became a site for a kind of still life, which was a bit like a commentary of my experience there. So there was all this popcorn that sort of maybe spoke to, like, the type of frenzied action, or the consumption of image.

I was working with my experience of that space transcribed into sculptural forms. And so, to get closer to the answer to your question, it was really when Chariots closed that I began to think a bit more about those interiors, through image. In 2016, which was a year after my ICA show, the building was squatted and I had a friend who knew the squatters, and so I was allowed in to experience it very differently to how I usually would. I documented the interior with a photographer, Mark Blower. So it was kind of born out of an urgency in a way of, like, spaces I was familiar with, spaces that I used, and trying to create a record of the interior. I never really saw those images as work in a way. What I saw as work was the kind of sculptures that I was making or the artefacts that I was working with that maybe came from the space, like these lockers, they're from Chariots, and they were left out in the car park with a sign that said 'Please help yourself'. And so I took them to my studio and I was able to sort of look at them differently there, outside of that environment. There's political commentary, as you see, or work by gay street artists like Paul Sheehan, or sexual health messaging, which was something I found to be quite important in a public space. So, yeah, they fascinated me on a personal level, but also I was able to look at them quite differently when I was looking at them through images, and it prompted a lot of other work, in a way. And so The Backstreet was somewhere that I was also going to around that time, but I never really approached any of this as a kind of, like, research or studious endeavour. You know, I was just sort of understanding that these environments were under some sort of threat, often because of gentrification. I am not the best photographer, so I wanted to bring the photographer along with me to take a record of these interiors. The Backstreet – there were rumours about its closure around 2017, which is when I took those images. And they'd always existed as a kind of resource, maybe for people writing their dissertations or they were published in some journals, but they were never really framed as sort of artwork in a way.

When the invitation came about to present them publicly for the first time, that's when I also thought about this other work, which was called Footnotes for Heros, which is on a monitor in the space, and that's comprised of a recording that I made in The Backstreet in 2015, so 10 years ago. But in revisiting it all this kind of text emerged as footnotes at the bottom of the screen. And the reason I titled it as such is because I recorded it from my foot. So in The Backstreet, I think it was kind of naked night, maybe, so I wasn't wearing very much and my phone was in my sock, so if it sounds a bit tinny, that's why. But then it's overlaid with kind of like 7,000 words of footnotes also kind of create a different type of image making from the sound, and that's shown alongside this slideshow of images and stools from the space. So I've often worked with kind of objects that come from these environments, repurposing them in a way.

Francesco Ventrella: I find it interesting that the project next door is titled Documents from a recent past. But then the sound recording with the footnotes is Footnotes for Heros. And you've told us that it's titled Footnotes because that's where you had [your phone], in a sock. But I was also thinking about the difference that is there between a document and footnotes. And I tend to think about a document as a text that is instructive, instructs something, has a sort of legal function, if you wish. And a document, of course, is also a memory, is a document in the archive that is a reminder of an historical event. And when we started to chat about this, I told you, you know, the idea of the footnotes works in a completely different way, because when we think about footnotes, we think about different voices that relate to the main voice of the text. But the footnote is a space where you can have a dialogue with other people, there could be other authors. And in your case, what happens in your footnotes is that there are different layers, different spaces, different voices. I don't know if you want to say something about the different spaces that you have created in your footnotes.

Prem Sahib: Yeah, I mean, I think the footnotes for me were a space to sort of take the viewer outside of what they might be hearing, so I sort of thought of that space as being capacious, in a way. But I also recognise, like, in academic fields, that they are kind of maybe a legitimising space. And so there was something about occupying those margins and maybe kind of introducing other more tangential material. It's quite vast in a way, because there's parts that are diaristic, there's parts that are anecdotal, but then there's also things that relate to, say, planning applications for the building or, you know, things I may have overheard in the recording, which I wanted to obscure, because there is also kind of ethics to consider in making this recording. When I made it, as I mentioned, I never really thought of it as becoming a work. I made it in the same way that I make other field recordings that somehow get used or sampled. But when I was invited to do this show, I realised that I had this 90-minute document, in a way. And so the footnotes became a kind of layer on top of that.

And then you notice that the screen is sort of completely black. So it's like not really giving the viewer a way into what the sound is describing, in a way, although you do see a kind of reflection of the images within that space. So, like you say, the body text that you might traditionally have as part of a document is obscured, but then in the margins or the trenches of the page or screen in this case, there's a possibility to sort of venture outside of where you're standing. And I liked also how this related to maybe how we experience reality through our phones, say, you know, being in scrolling and being in different places at once, so there is a sense of that and a sense of oscillating between different environments, spaces, histories.

Francesco Ventrella: Yeah, there is. Maybe I can read one of these footnotes, because it really gave me this feeling of overlapping of spaces, but also this one brings together desire, nature and the police: "I was too stressed to go home, so went for a cruise in the forest and saw a startled baby Muntjak deer deep in the bushes. In my excitement, I told the plainclothes police officer who I had just met there. He confirmed that you do see them sometimes." And I was interested in the fact that this being a footnote is not a caption to the sound recording. Footnotes and captions work in a completely different way, but at the same time it makes reference to the intertwining of three different spaces: nature, desire, cruising and the police. That is always there.

Prem Sahib: No, exactly. And it's a completely different space that I'm describing, but it kind of remained with me as a residue in a way. So I think I'm thinking a lot about residues, in a sense or kind of echoes of being somewhere and thinking about elsewhere. And so, yeah, that was another cruising site, which is close to where I live, which actually has been completely felled now, so it doesn't really exist in the same way anymore. But there is this distinction between places like The Backstreet, which is a commercial cruising venue, places like the forest which aren't. But also what was interesting to me is this is a gay-owned venue, you know, unlike Chariots, which was also kind of more of a business enterprise, I think.

Francesco Ventrella: It’s like if you manage to catch the recording between footnotes 37 and 43, this is really interesting because it is a number of footnotes that really takes you from the cemetery in Tower Hamlets, that still is a cruising ground, and the memory of Rajith Kankanamalage who was killed around 2015, around that time. And then there is a description of experiences, feelings, things that had to do with, you know, being in the bushes, being in the cemetery, that slowly, slowly merge into other sensory experiences of opening the door of The Backstreet. And then all of a sudden it feels almost as if the experience of being in the cemetery is carried in the open space, is carried into this closed space of The Backstreet. And I want you to comment about this transition, but also because you really have a strong feeling that we do carry, maybe this has to do with queer experience of desire, sex and sexuality, that we do carry certain things from one space onto another. And we also carry certain memories of violence with that when we move through these spaces.

Prem Sahib: Yeah, I think it was definitely that. And also, you know, I think for me, these spaces are nuanced, complicated spaces. You know, in some respects they're like home from home and really familiar and feel safe. And then there's also things that can occur there that are not sometimes, you know, far from ideal. And so I think I try and figure that into making an archival document in a way. Oh, I like how an archival object or document can maybe speak to some of those things. And so this idea of safety and the other neighbouring cruising site being the site of a murder was important for me to sort of carry into this space where I did feel sort of protected behind these doors. And actually I have the doors of The Backstreet in my studio, because when they closed, a lot of objects went to The Bishopsgate Institute and to The Museum of London. And then they opened up the rest of the objects to people that used to go there to take away or to buy. And they kindly gave me the doors, which I will, I hope, use as part of a work one day.

But they have all these egg stains on the outside which are because of homophobic attacks. So they're quite interesting objects in that they speak to a hostile outside world and then somewhere where people felt safe. But, yeah, in trying to think where I could put some of those feelings in the recording, I kind of just maybe say a bit about the process of how I made it. I kind of mapped out – I did a drawing in my sketchbook of The Backstreet, and I was listening to the recording a lot. And I was trying to think about the different kind of spatial environments and where felt appropriate for certain materials. So, like, some of that stuff, which maybe you could think of as being a bit darker, didn't feel quite right or congruous with the amazing playlist that is also archived in this work. So some things stay in the kind of smoking area where you hear the fans or they kind of are slightly stepping out of the space, but then kind of close to it, you can hear the kind of reverberation of the sound and then you can hear me moving and travelling around the space.

Francesco Ventrella: Yeah, I think sound is amazing. And we've not said that the DJ, do you remember the name of the DJ there? No, I don't. But yeah, they are amazing 1990s bangers that also speak to my generation, our generation, I am kind of a bit older than you, but our generation. And yeah, I think that is an archive within the archive. Maybe we could sit a bit with feelings and the sensory experience, especially because at least in my work and in my teaching, you know, when I teach students and we discuss queer archiving, you know, one of the problems that we encounter is that there are no official institutions, historically speaking. You know, queer experiences, queer material culture has not been consistently documented, it's not being consistently archived. And most of the time, instead, we seem to latch on feelings and sensory experiences that we associate with particular objects. And then it's the feeling that becomes an archive in itself rather than an institution, you know, that houses these things. And there are two moments in in the Footnotes in which you make a string of all the names of the nights organised and the themes of the nights organised at The Backstreet: Buff, Mega Buff, Bluff, Ignite, Rubbered, Down and Dirty, Gentlemen and Heros, of course.

And that really, it's like there is a sensory element, obviously, to these names. And then early on in the sound recording, there is this 'ping' and it's the oil drum, which is now in your studio. You described the way in which this oil drum changes in relation to heat levels in your studio.

Prem Sahib: Yeah, it was one of 24 or 25 oil drums, I think the owner rolled from somewhere along the canal to his flat to paint black, to go to The Backstreet, which one of which eventually ended up with me and Mark, who ran the place later, told me that: "Oh, you have the one that pings". So I think it was unique in that sense. But yeah, just this idea of kind of like heat and cold and comfort and closeness, all those ideas, it seemed to offer something poetic in a way. So when the sun comes into the studio and it heats up, that kind of releases this kink in its vessel. And so I just really liked how it kind of played a sound of the space outside of it, almost. And how there's, like, a biography to some of these objects, which is initially why I've worked with objects in a way.

Francesco Ventrella: Another thing that we talked about before, in those nights where we chat about things, is the element of nostalgia or attachment. I remember we told each other once: "Okay, but, you know, is nostalgia the right mood for queer archiving?" We felt that there was something, I don't know, insufficient about it, but we couldn't really put the finger on it, and I don't think I still can. But there is definitely a strong element of attachment to certain objects, to certain sensations and feelings that comes across in your work. And I don't know if you want to say something about that.

Prem Sahib: I can't remember what I would have said about it. It's probably different to what I'm about to say.

I guess maybe I was anxious about it only being nostalgic or something. And I wonder whether I feel like nostalgia can also be a raising of certain things because there's a sense of idealism in looking back at something with a sort of fondness. So I think maybe I don't feel like it's quite the right word, and maybe that's why it sits a bit uneasy, and perhaps that's why I wanted there to be something that kind of complicates what you're looking at that can kind of remind you of a different positionality. Even the fact that I first made this Footnotes work as a kind of work in progress, it kind of made me feel quite content that, you know, things can change or there isn't a sort of fixity in a way.

Francesco Ventrella: I think this is also because of speaking to other people, other friends who've been to The Backstreet. You know, there is nostalgia, but there is also, from the people who've been there, a sort of attachment and not authority, but, you know, wanting to be the people who remember the place in their own words, which is absolutely an important element of an archive. But then I'm also thinking about the stickiness of these objects becoming almost a metaphor of the way in which we get stuck with them and maybe for me, another name of nostalgia could be, you know, we get stuck with certain objects. You know, I've been doing work on Section 28 and I got stuck. I wasn't in the UK during Section 28. It's part of my research, but I got stuck with those particular objects. And even touching them is something that has informed my thinking. You mentioned orientation, and we're both fans of Sara Ahmed, and I think that is another reason why we bonded is that we both share an excitement for Queer Phenomenology. And you don't mention many books in your footnotes.

I can't remember now, but that one is definitely something that you quote from. So in that case, the footnote becomes the space for a quote. And you're interested in what she says about orientation. So without wanting it to be a test, you know, what have you found in Queer Phenomenology that you keep going back to?

Prem Sahib: I think it's more a question of like, embodiment really. And I think what I like about her work is that she alerts you to there being, there's not a kind of universal body experience. And I think sometimes me reflecting on these spaces, it can sometimes feel like that. For instance, you may have seen this relief of a kind of plaster relief from Chariots.

Francesco Ventrella: The neoclassical one.

Prem Sahib: Exactly, yes. Of this kind of Greek God, Nike, awarding this athletic white body. And so I was sort of thinking about how those ideas around, kind of like, who are spaces for? Or a kind of establishing a sort of somatic norm from which everything is viewed through, is thought about. And like I said, like this one, this is in Chariots.

Francesco Ventrella: Yeah.

Prem Sahib: And so I made a cast of this, for instance. I know I'm sort of kind of going off on a tangent here, but.

Francesco Ventrella: Oh, is a cast the one that is in the tape?

Prem Sahib: Yeah. So it's again, going back to this idea of authenticity. It's not an original, it's one that's cast. And then I sort of prized it from the wall, from this space of permanence and with these giant piercings in a kind of iconoclastic way interrupting that image or weakening it somehow. So I think what I like about Sara Ahmed's work is this kind of discussion of how things like race and gender figure into an experience as well, which maybe relates to this whole idea of an archive being a kind of master document or something, you know?

Francesco Ventrella: Yeah, yeah. I wonder if the work is later, after the photos or before with the lockers?

Prem Sahib: Yes, it's just before these ones.

Francesco Ventrella: Just before. Maybe that would be good to think about. So you mentioned already, this is one. These are the lockers from Chariots and that you were able to take. And the title is Do you care? We do. And I remember being really struck by this opposition between we and you. I wanted you to comment about the way in which you have arranged these lockers and what it implied, you know, taking them, decontextualising them. What do you think you have gained or lost, and what kind of things remain from Chariots originally and what other things instead get lost and that can be gained by bringing this work into an art gallery? And now, I think, is in the Tate collection, right?

Prem Sahib: There's a lot of detritus in them. There's also a lot of, not very much in them, which I think makes you look at their surface a lot, and the kind of dents and scratches and kind of thinking of what they may have endured as objects, but also, like this space in which people leave their possessions and navigate that space differently, you know, to how they might in the outside world. So it is really my interest in these spaces is also about them being the space between work and home. In terms of how they're arranged, most of them have their doors open, so I think there's a kind of openness to what they might be trying to share or say. And they're quite figurative on these prints. The title comes from a condom campaign from the 90s, which I found as a sort of sticker in a lot of the lockers, which the slogan was, 'Do you care? We do' and so I just like this implication of how you navigate being a kind of individual amongst a community and then this idea of care as well.

Like you say, they've kind of ended up in an institutional collection. But I was sort of thinking about who does that archival labour initially, from taking these as discarded objects in the car park into a space and giving a certain type of attention or new framing to look at or importance, and then who continues that work? I also showed them alongside a replica of my first birthday cake, which seems like a surprising thing to have in contrast, but just harking back to that idea of being individual and in a community and navigating those two different spaces.

Francesco Ventrella: And I don't know if this is a question or more of a comment, but I find that in your work, you work with sex as something that is not private, it's not secret, it's not intimate, but it is public, it is social and socialised and it has to do with the every day, rather than something that, you know, in a heteronormative, mainstream way, would be behind closed doors. Should I turn this into a question?

Prem Sahib: Yes, please.

Francesco Ventrella: Is there something that you think resonates with your attempts to move things across different spaces? Maybe this is a question about the art gallery, the gallery space. What do you do with it?

Prem Sahib: Yeah, it is a really interesting question. I make sculpture, so I think I'm really attracted to the kind of weightiness of things, even the weightiness of these moments that I might see or encounter, the kind of weight of certain archives and histories. I think moving them or recontextualizing them does allow us to look at them differently and sometimes outside of themselves. I haven't done this very often, but on one occasion I did recreate the whole environment of one of these clubs. And that was quite strange to see that in a gallery space, because usually exists as a men-only cruising club. But I was really interested in this kind of, quite highly orchestrated image that I wanted to recreate. And so you step into the gallery and you're transported there. But I think I've always been aware about giving audiences, or not giving audiences, just a sort of titillating glimpse into those worlds. So I think maybe that's why I've used things like abstraction in the past. And then it's very kind of case by case with what I feel like I want the work to be doing in a way.

Like there are residues of this that speak to places like The Vault, because these are the types of baskets that you get given to leave your clothes. But then objects like the blanket, which is a kind of fake fur on one side, and then men's shirting on the other, which I was looking at and it made me think about kind of cages and bars worn on the backs of men. So they kind of also become opportunities to talk about things outside of that space too. That kind of shifting of them from one environment into another.

Francesco Ventrella: Yeah, thank you. If we could go backwards just a bit, there was that black screen, because I'm interested in the voice in contemporary art, but also in resonance. You've done a few works now with voices, on the voice and, next door, obviously is a field recording, technically, but there are some voices that you have slightly altered because you didn't want necessarily people to feel or be recognised. But this work here, which is made with black obsidian.

Prem Sahib: That’s right, yeah.

Francesco Ventrella: And it's a work that also has, inside, a recording of an exchange that you had with someone online. So online being another space. And because perhaps it's so hard to understand how the work works, maybe do you want to say something about it?

Prem Sahib: Yeah, sure. So I've worked with voice on a few occasions. I feel like there's many voices in the Footnotes work, for instance.

And then in this one, it's a mirror made from obsidian, which is like a volcanic glass that's been polished to resemble a kind of screen in a way, almost like the kind of cracked screen of a communication device. And within it is this speaker, a sound exciter, that plays a monologue I recorded in a gay chat room of someone who was being homophobic and racist. And I don't record myself, you just hear me typing, but I'm showing him my body and I'm recording his response. And I was very conscious of not giving more space to that hate speech. So I abstract it by stretching the material quite sculpturally and then it just exists as this very growly, kind of ominous sound that emits from this black mirror. So you don't actually hear the recording, but it still exists. I think I was going back to that thing about moving something from one space into another, sort of thinking, how can I work with this material while not giving it, while not recentering it or something, but kind of maybe the material itself speaks to sort of trauma and heat and pressure and some sort of violence, or at least that the material, obsidian, speaks to me in that way.

And then more recently, I've worked with the voice of Suella Braverman in a similar way, but rather than hate speech administered by an individual behind a screen, I was thinking more about a public figure. With that work, I used a speech that she made in the House of Commons about the so-called "Illegal Migration Bill" and I did things like reverse it to sort of mirror her sentiment of sending back the boats and that became a performance more recently, so it was performed by vocalists. So a bit like a way to further fracture that voice and break it down, but also to think about how that sentiment exists, or as it moves through society more broadly.

Francesco Ventrella: Yeah, yeah. And I think this is interesting in this idea that certain bad feelings, you know, seep through society very often alongside spaces and environments in which we seek pleasure, as in this case, the chatroom. And I think that the work, the way in which you have used voice is almost to enhance this kind of splitting and so that you can recognise these different channels.

Prem Sahib: Yeah. Like, I feel like some of the earlier work, I felt like was maybe not celebrating, but maybe thinking about those spaces in a different way. And then there was a point where I kind of wanted there also to be more of a criticality, that was perhaps I felt maybe more honest to how I experienced those spaces or encompassed things that might feel difficult to talk about. And I felt like art was a good place for that.

Francesco Ventrella: Yeah, and I think that is important, in the era of alleged, you know, gay rights and gay marriage and so on and so forth, to be reminded of the things that we carry with us, but also that the spaces that we cross are complex and complicated. I think that in mainstream culture there is a lot of emphasis on, you know, queer joy. And maybe we are a bit of… two killjoys.

Prem Sahib: Killjoy. Exactly.

Francesco Ventrella: Should we end it there? Yeah.

Prem Sahib: Thank you.

Francesco Ventrella is associate professor in the Department of Art History at the University of Sussex, where he is also affiliated with the Centre for the Study of Sexual Dissidence. He has written on the history of art writing, and its relation to affect, resonance and the voice. His work has been published in Art History, Studi Culturali, British Art Studies and European Journal of Women’s Studies, and with Giovanna Zapperi he has edited the volume Feminism and Art in Postwar Italy: The Legacy of Carla Lonzi (Bloomsbury, 2020).

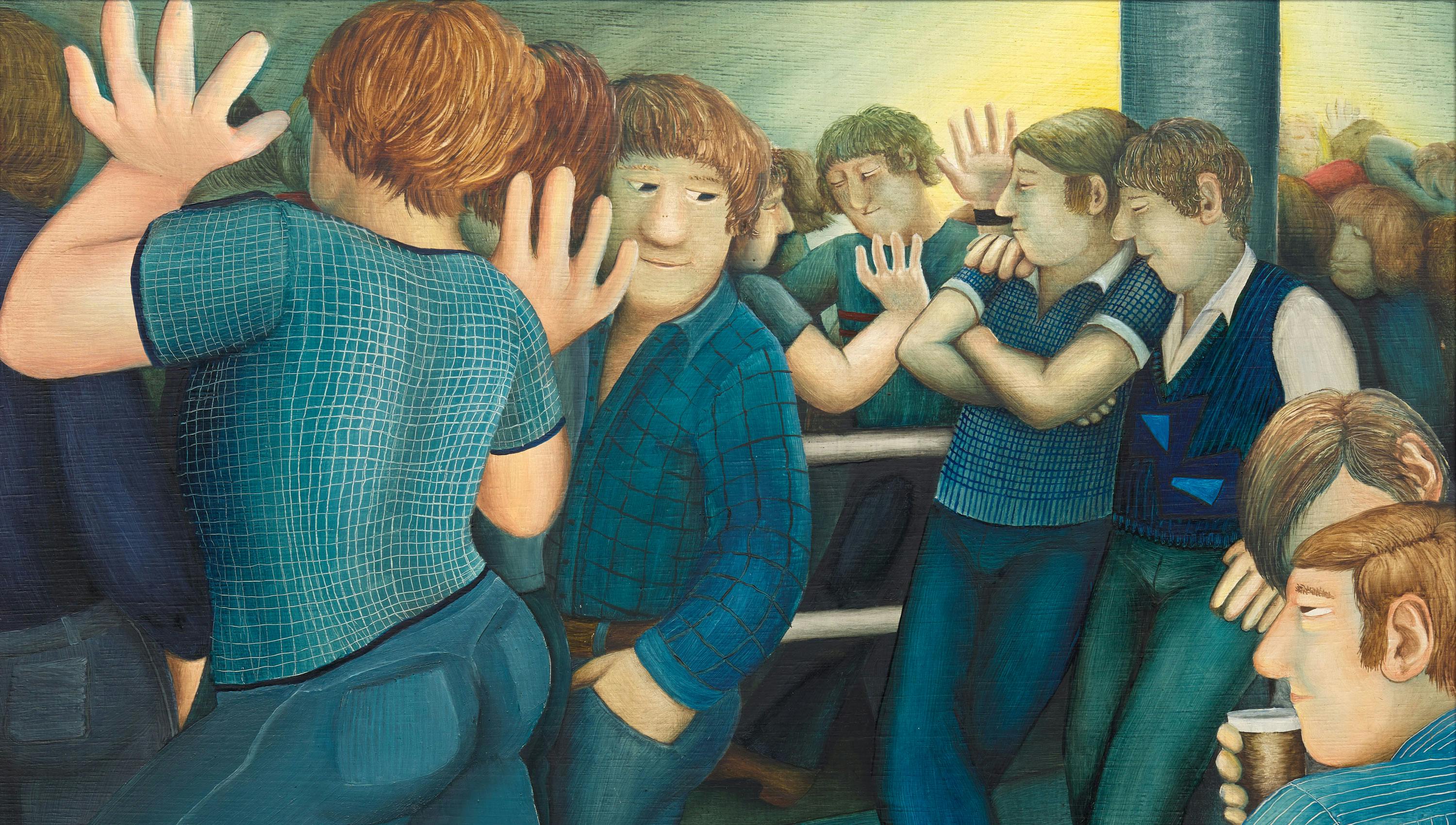

Prem Sahib, The Backstreet, 2025. Image courtesy of the artist and Phillida Reid, London. Photography by Prem Sahib and Mark Blower.