Alex Margo Arden is an artist from London. She creates multilayered performances, installations, and odours. Previous projects have been presented at Ginny on Frederick, London; Cell Project Space, London; La Casa Encendida, Madrid; World Pride 2021, Malmö; The Royal Standard, Liverpool; Mathew Gallery, New York; AND/OR, London; Serf, Leeds. She is currently a student at the Royal Academy Schools, and previously graduated from Goldsmiths where she was awarded the Hamad Butt Memorial Prize.

Hollywood Babylon

An evening of readings

Artists, writers, and performers read a selection of materials celebrating the idiosyncratic pantheon of public figures and Old Hollywood stars found within Scott Covert's exhibtion C'est la vie. Contributors included Alex Margo Arden, Hannah Regel, Lauren John Joseph, Misha MN and Sam Cottington.

In response to Covert's highly personalised taxonomy of famous subjects, the readings for this event delved further into the various themes of 20th Century American pop culture, relating to ideas of celebrity, gossip, mythology, representation, and tragedy.

This evening of readings takes its name from the highly popular, highly gossipy book Hollywood Babylon by avant-garde filmmaker Kenneth Anger, published in 1959. Comprising untrue and exaggerated short stories, Hollywood Babylon details the alleged scandals of stars from the 1900s to the 1950s, many of whom feature throughout Scott Covert’s long-standing series of Monument and Lifetime drawing works — featuring the likes of Babe (Barbara) Paley, Bette Davis, James Dean, Joan Crawford, Florence Ballard, Marilyn Monroe, Nancy Spungen, Ramon Novarro, Rock Hudson, Sylvester James, and Warhol superstars, Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis and Edie Sedgwick.

Transcript:

Alex Margo Arden reads Culture, Celebrity, and the Cemetery: Hollywood Forever (2018) by Linda Levitt

I'm going to be reading some sections I've edited together from Linda Levitt's ‘Culture, Celebrity, and the Cemetery: Hollywood Forever’, which was published in 2018 but was written in 2008. I've been working from an older manuscript, so I don't know if it's even in the final published book, but we'll see. Also, it's got a specific reference to Florence Lawrence and Rudy Valentino — and at the end I'm going to read a short extract from Kenneth Anger's ‘Hollywood Babylon’ as well.

Hollywood Forever: The final resting place of celebrities and notable public figures Clifton Webb, Florence Lawrence, John Huston, Moe Sedway, Nelson Riddle, Peter Finch, Peter Lorre, Richard Blackwell, Rudolph Valentino and Victor Fleming, among others. The Hollywood Forever Cemetery in Los Angeles has served as a tourist attraction and a site of public memory. In 2017, superstar Judy Garland was moved from her original burial spot in New York to the new 'Judy Garland Pavilion', built for her at Hollywood Forever.

All of the aforementioned people are featured in the Scott Covert Works on show here today.

Culture, Celebrity, and the Cemetery:

The name Florence Lawrence is not widely known, and it was not known at all at the beginning of her Hollywood career. Yet Lawrence, who was buried in an unmarked grave at Hollywood Memorial Park in 1938, marks the beginning of the star system and celebrity culture as we know it. Actor Roddy McDowell, who was a collector of celebrity memorabilia, gave her a grave marker in 1991, and Carl Laemmle gave her a name in 1910. In cinema's early years, actors were not credited by name, and Lawrence, who had signed to Biograph with director D.W. Griffith, became known as 'The Biograph Girl'. She was hired away by Laemmle, who gave her individual billing, making Lawrence the first star to be known to the public by name. Yet Laemmle wanted to ensure that her name would be familiar to the movie-going audience.vIn what was widely considered the first celebrity publicity stunt, Laemmle planted a story that Lawrence had suddenly died. Soon after he retracted the story and Lawrence made an appearance in St. Louis, well received by an adoring crowd that may have not given her much thought before their vicarious emotional involvement in her fabricated death and resurrection.

Lawrence reentered cultural memory at the 2006 Dia de los Muertos celebration at Hollywood Forever when a group of four friends built an altar in her honour. Sandy, a set designer, worked with her husband Matt and their friends Trevor and John to create a papiermâché skeleton surrounded by enormous intertwining strands of film stock. Strewn about the film strands were dozens of gigantic Styrofoam ants, a reminder of Lawrence's unfortunate suicide resulting from a combination of cough syrup and ant paste, which contains arsenic. Alongside this somewhat morbid scene, however, was a continuous looped reel of Florence Lawrence clips. Situated just outside the Cathedral Mausoleum, the altar drew the attention of many passersby who were introduced to a forgotten Hollywood star. Sandy and Matt, who live within walking distance of Hollywood forever, created altars commemorating Janet Gayner, Rudolph Valentino and Douglas Fairbanks. For a previous Dia de los Muertos celebrations, she says the group deliberately chose Florence Lawrence because of her relative obscurity and the desire to bring her work to a broader contemporary public.

In the Cathedral Mausoleum, several of the skylights had cracked and broken away, letting the rain stream in. Even the stained glass windows were broken in several places, including one in the Valentino Alcove. Cobwebs and dirt became commonplace in the corridors and it was obvious that no upkeep of any sort was being maintained within the mausoleum.

In this bleak setting, mourning was perhaps a more prominent feeling than celebration for Valentino's life and career. Yet such mourning would be tinged with nostalgia, not only for Valentino himself, but also for a long history of memorial services in his honour and the touch of glamour that once accompanied them. Dignity, if not glamour, has been restored to the memorial services, along with the restoration and renovation of Hollywood Forever.

Despite the many changes at the cemetery, there is one constant: the ever-present Lady in Black, a role played and contested by several women over the past 80 years. In the 1920s and 30s, part of the media's interest in the anniversary of Valentino's death was to discover whether the lady in black would pay her respects, kneeling in prayer before Valentino's crypt and leaving flowers in honour of the great lover. This mysterious woman, clad entirely in black with a veil covering her face, began paying an annual visit to the cathedral mausoleum on the second anniversary of Valentino's death. But there was more than one Lady in Black. In 1937, at the 11th annual memorial service, a second veiled woman appeared at the mausoleum, adding another dimension to the story of the devoted fan. Mausoleum caretaker Roger Peterson, along with reporters and photographers who had seen the Lady in Black over the years, had contradictory descriptions of the mysterious woman. Thus it was clear that there were several ladies in black. And as the character gained notoriety, any Valentino fan or publicity seeker could easily perform the role of a woman who chose to hide her identity behind a black veil.

In 1941, the curious public would get its answer, or at least one answer, to the identity of the Lady in black. After leaving flowers at Valentino's crypt, Ditra Flamé laid claim to being the woman who had been mourning there for 15 years. Flamé told us a story of how as a teenager she was acquainted with Valentino before he was famous, struggling to make ends meet at a boarding house in Los Angeles. When Flamé was admitted to hospital for an abscess in her ear, Valentino came to visit her. She told him that she was afraid she would die and he consoled her. Flamé claimed that she and Valentino had made a pact in which she promised that he should die before she did. If that were to happen, she would remember him with a single red rose on the anniversary of his death. She found the Hollywood Valentino Memorial Guild and devoted herself to maintaining and promoting the public memory of her idol. She fervently upheld her role, seeking status both as a dedicated fan and as a person with privilege in the Valentino legacy, since, as she claimed, she had promised him that she would always perform these acts of commemoration.

Another former acquaintance of Valentino who claimed the role of the lady in Black was Marion Benda, who was his date on the night he fell ill in New York City. She appeared once at Valentino's tomb on the anniversary of his death, dressed in black, and refused to speak to the media. So there was evidence that she had performed this particular role. Yet her claim that she was a mysterious visitor who appeared each year was easily dismissed. After a quick bit of research, we can reveal that Brenda had been living abroad for 15 years since Valentino's death. Benda's story is an unfortunate one. In addition to claiming that she had secretly married Valentino and born two of his children, Benda attempted suicide several times. When she finally succeeded in taking her own life in 1951, newspapers reported that Valentino's Lady in Black had died, much to the chagrin of Ditra Flamé.

New Ladies in Black continued to appear at the Valentino memorial services over the years, but none rivalled Ditra Flamé for their notoriety until Estrellita Del Regil arrived at the 1978 memorial. Where Flamé strove to attain a dignity on Valentino's behalf, Del Regil earned her reputation among the Valentino memorial regulars for her outrageous antics. She claimed that her mother was the original lady in Black and that Valentino was in love with her. When her mother died in 1973, she was buried at Forest Lawn by mistake, according to Del Regil, who had disinterred and then moved to Hollywood Memorial Park. Among Del Regil's acts of commemoration were placing large black paper stars with Valentino's name in gold glitter in the corridor leading up to his crypt and using black electrical tape to place red roses on the crypt surrounding Valentino's. Like Flamé, Del Regil assumed an error of privilege as the lady in Black, but the Valentino crowd considered her an impostor who disrupted rather than complemented the memorial services.

Del Regi attended her last memorial in 1994 and a new lady in Black, Vicky Callahan, took on the role the following year. Callahan publicly considered herself the third generation Lady in Black. Rather than vying for a place of honour, she intended to pay tribute to the dedicated fandom of those who came before her. Despite her tenuous but authentic connection to Valentino, her high school drama teacher was Walter Craig, who used the stage name Anthony Dexter when he portrayed Valentino on film. Callahan, who could do no more than perform the role she is, to use Joseph Roach's term, the Lady in Black in effigy. For Roach, performed effigies provide communities with methods of perpetuating themselves through specially nominated mediums or surrogates who stand in place of the absent original. Callahan's mournful, self conscious appearance at the Valentino memorial recalls and brings into being the history of ladies in black who came before her. As she walks through the mausoleum to lay flowers at Valentino's grave, she literally follows in the footsteps of Ditra Flamé, Marion Benda and Estrellita Del Regil evocatively embodying the past for those gathered to pay tribute to the silent film star. Her parodic performance of mourning is saved from being comedic because of its symbolic effect of representation that extends far beyond Callahan herself.

At the 1995 memorial, Callahan was among a handful of guests dressed as the Lady in black. She stood out among the others, she said, because of her kitschy accessories. "I had two name brooches which spelled out Rudolph Valentino in rhinestones. The writing is done in elegant cursive style. They sparkled like mad on my black velvet handbag. Even caught the camera's eye a number of times. Rudy's name was once again in lights", she says. For Callahan and for others, camp appreciation plays a discernible role in the performance of Valentino fandom and commemoration. Although Hollywood forever designated Carrie Bible the official Lady in Black at the 2002 Valentino memorial service, women still come to the services dressed in vintage black dresses and veils, both in homage to Valentino and also to carry on the tradition themselves.

Hollywood Babylon:

There’s a New Star in Heaven Tonight — R-u-d-y V-a-l-e-n-t-i-n-o.

Valentino’s demise at thirty-one left inconsolable paramours of both sexes, to judge by the tear-streaked testimonials. Aside from the “Lady in Black” bearing flowers annually to the mausoleum on the anniversary of his death, the memory of Rudy was cherished by Roman Navarro, who kept a black lead Art Deco dildo embellished with Valentino’s silver signature in a bedroom shrine. A present from Rudy.

- Linda Levitt, Culture, Celebrity, and the Cemetery: Hollywood Forever (2018) New York: Routledge

- Kenneth Anger, Hollywood Babylon II (1984) London: Arrow Books

Sam Cottington reads from People Person (2022)

I'm going to read from my novella called ‘People Person’. It's told from the perspective of Charlie, who moved to London to study art and dropped out. He couldn't find a way to make it work for him, but he still is approximate to the art world, attached to it, I would say quite painfully. He's miserable. So the book is set over one weekend, but it's interrupted with short chapters where he gossips about his friends or introduces these characters to the reader. So I'll start with the opening short chapter and also I'm trying to turn this into a play and I think of the play's title as like a secret title, and the play's title is ‘People in Hell Just Want a Drink of Water’. But I couldn't call the book that because that's from a short story. So I'm going to start with Clara, which is the opening short chapter.

People Person:

Clara hated homeless people. It was so obvious, but I didn't know her well enough to bring it up, even though she was always around. She was dating a friend of Ralph's, but I wasn't sure which friend. It felt odd describing her as a friend because we hardly knew each other and I really didn't care about her. But she hung around us and everyone thought we were friends and it would seem immature to insist that she wasn't my friend. She wasn't just inconvenienced by homeless people. She would tense up completely when they spoke to her, swallowing her frustration, practically seething, it was weird to see her like that. The rest of the time she was so smiley and cloying with people. If you had a bad day and you told her about it, her mouth and eyes would turn to O's at every twist of the story, watching you breathlessly. People liked that about her. They knew they could get the reaction they wanted. She tried to hide it. Her anger at filthy, wandering street people. And all her hair and her hat, feigning coy, tilting its brim like a court fan. You have to admit that's a little psychotic, folding your hat in front of someone to block them out.

She always wore that hat. Brown felt with clean brown hair underneath it. The hat was pretentious, worn by so many people in those days. Gay men wore them when they wanted to wear women's clothes. Wearing one afforded some of the perceived glamour of a wide brimmed hat. The structure and extension, people and things disappearing from view. But you probably wouldn't be beaten up in the street for wearing one. Or if you were, you probably would have been beaten up anyway. And for women, it was a blank symbol of history. The 70s, the past, autumn, when looking at Clara, the word retro sprung to mind. It was frustrating, honestly, because for her it was a comfortable way to appear - to appear remarkable, as in to be literally remarked upon, not wonderful or noteworthy. Look at me, she wanted to politely demand. A desperate attempt at an image that would make an impression that instead gave her the feel of a memory you couldn't quite grasp and didn't want to. Some of the faceless junk in your head that could be the scraps of a dream or a shit picture you saw in a magazine once. There was no style, no passion or connection to something underneath her hat, only hair that grew so simply from her scalp.

She came across as a nice, fun girl, mostly, except for moments late at night when we were all out together. She would sometimes switch off like a light found sitting alone somewhere. When she met your eyes in this mood, they would seem desperately amiable with the impression of having waded through tears and mud and grey river slime to reach you. She would deny that anything was wrong if you asked her.

So the momentum of the book is over this weekend and basically what happens is people tell him what he does when he blacks out. And as the book goes on, it becomes more and more of a problem for Charlie. I'm going to read a bit, which is so he's like, gone out. He's blacked out. He's on his way to go out again and his mum texts him that she's found a picture in the loft and it reminds him of this thing that was like a really stressful thing that happened to him when he was a teenager involving his mum and pictures. Okay.

When I came home from school one afternoon, my pack of printed photos were on the kitchen table with Mum and dad on opposite sides. Dad had come home from work early. My mum took the glossy printed photos out of their paper packet and placed them out across the table. Me and my friend's frozen jaws were outstretched and laughing. Alien expressions in my mother's wrinkled fingers, shuffled like a deck of cards. I don't know why I took the photos. I never thought of them as art or serving any purpose. It just seemed like something to do, an activity for when we got drunk. We went to fields or each other's houses, rarely a club or a party. We were a weird group: three very tall girls, one very short girl and a shy, ugly boy. That was me. We drank from bottles with bright coloured mixtures of sugar and alcohol, or full on bottles of spirits and high percentage cider. We didn't mind. We wanted as much as possible, as quickly as possible. In the fields we tipped the bottles into our mouths and spun in circles. We didn't only get drunk, it was way more than that. We wanted to pass out and hurt ourselves, to disappear, to vibrate into nothingness without thoughts or direction.

Throwing up didn't matter. It was funny. Falling out of trees was funny. Passing out on the pavement with bloody, filthy knees, being carried into the woods or to hospital. We found it ridiculous and we enjoyed the sensations it brought up. Sickly, unknowable feelings that were kind of luscious when we really indulged in them. We shouted the worst things we could think of from the top of our lungs. We threw empty glass bottles at crows and sleeping horses. The photos my mum saw were definitely the peak of our experiments, taken when my head was white lightning in a pitch black field. The first few were just grass and mud lit up like crime scene photos. Feet and legs in the corners of the frame, trainers with ankle length socks. And then, in a rush, the photo montage focused on faces covered in vomit, clear alcohol being poured on the mouth of a sleeping girl and then stepping down into a cellar, black voids of field behind bright white fingers nesting in orifices. The girl who had passed out, but also the other girls who were awake but not fully, had reached that lucid dreamy state of drinking, when you're first getting drunk and it feels like a huge relief and it's brand new and exciting and vital, like taking a powerful drug for the first time. I took part, but I wasn't subjected to the invasive examinations. No bright, blurry hands poked inside me. I don't know why, I guess because I was the only boy. Doing anything like that to me was too dirty to imagine at that age, 14 or 15, I think, maybe 13, my slender fingers were hardly distinguishable from the girls, but still recognisable. A slightly squarer palm, flecks of hazel hair at the wrists and up the arms. No nail polish.

I'll leave it there, thanks.

- Sam Cottington, People Person (2022) London: JOAN Publishing

Lauren John Joseph reads A Queer Feeling When I Look At You — Hollywood stars and lesbian spectatorship in the 1930s (1991) by Andrea Weiss

Hello, I'm Lauren John Joseph and I will be reading this evening from a chapter called ‘A Queer Feeling When I Look at you: Hollywood Stars and Lesbian Spectatorship in the 1930s’ by Andrea Weiss, which is featured in ‘Stardom: Industry of Desire’ (1991) by Christine Gledhill.

A Queer Feeling When I Look at you:

Boldly claiming to tell the facts and name the names, in July 1955, 'Confidential magazine' embarked on telling the untold story of Marlene Dietrich. The expose reads 'Dietrich Going for Dolls' and goes on to list among her many lovers the 'blonde amazon' Claire Waldoff, writer Mercedes D'Acosta, rumoured to be Greta Garbo's lover as well, a notorious Parisian lesbian named Frede, and multimillionaire Jo Carstairs, whom 'Confidential magazine' dubs a 'mannish maiden' and a 'baritone babe'.

The scandal sheet may have shocked the general public by its disclosures, but for many lesbians it only confirmed what they had long suspected. Rumour and gossip constitute the unrecorded history of the gay subculture. In the introduction to 'Jump Cut's' Lesbian and Film issue, the editors begin to redeem gossip's lowly status: "if oral history is the history of those denied control of the printed record, then gossip is the history of those who cannot even speak in their own first person voice." Patricia Meyer Spacks in her book 'Gossip', pushes this definition further, seeing it not only as symptomatic of oppression, but actually as a tool which empowers oppressed groups. Gossip embodies an alternative discourse to that of public life and a discourse potentially challenging to public assumptions, it provides language for an alternative culture. Spacks argues that through gossip, those who are otherwise powerless can assign meanings and assume the power of representation. Her concept of gossip as the reinterpreting of materials from the dominant culture into shared private values could also be a description of the process by which the gay subculture in the United States in the early 20th century began to take form.

Something that, through gossip, is common knowledge within the gay subculture is often completely unknown on the outside, or, if not unknown, at least unspeakable. It is this insistence by the dominant culture of making homosexuality invisible and unspeakable that both requires and enables us to locate gay history in rumour, innuendo, fleeting gestures and coded language. Signs I will consider as historical sources in order to examine the importance of the cinema and certain star images, in particular in the formation of lesbian identity in the 1930s.

By the time her unspeakable sexuality was spoken in Confidential magazine, Marlene Dietrich was no longer a major star. She had not yet stopped making movies, but she was not a major box office draw in the United States and would soon return to the European cabaret stage on which she began. The appeal of her sophistication, her foreign accent and exotic, elusive manner had been replaced by a new, very different kind of star image, that of the 1950s all American hometown girl, exemplified by Doris Day and Judy Holiday. Had the article been published in the 1930s, when Dietrich was at her peak, it may well have cut her career short. The studios went to great lengths to keep the star's image open to erotic contemplation by both men and women, not only requiring lesbian and gay male stars to remain in the closet for the sake of their careers, but also desperately creating the impression of heterosexual romance, as MGM did for Greta Gabo in the 1930s.

But the public could be teased with the possibility of lesbianism, which provoked both curiosity and titillation. Hollywood marketed the suggestion of lesbianism not because it intentionally sought to address lesbian audiences, but because it sought to address male voyeuristic interest in lesbianism. The use of innuendo, however, worked for a range of women, spectators as well, enabling them to explore their own erotic gaze without giving it a name and in the safety of their private fantasy in a darkened theatre. Dietrich's Rumoured lesbianism had been already exploited in this way by paramount's publicity slogan for the release of 'Morocco'. Dietrich — the women, all women want to see. This un-naming served to promote intrigue while preventing scandal. Lesbians may well have suspected, for example, that Mercedes D'Acosta and Salka Viertel were the great loves of Greta Garbo's life. But the general public only remembered that she once agreed to marry John Gilbert. (Garbo used to answer Gilbert's many proposals of marriage with "you don't want to marry one of the fellows".)

What the public knew, or what the gay subculture knew about these stars 'real lives, cannot be separated from their star image. For this reason, I am not concerned with whether the actresses considered here were actually lesbian or bisexual, but rather with how their star personae were perceived by lesbian audiences. This star persona was often ambiguous and paradoxical. Not only did the Hollywood star system create inconsistent images of femininity, but these images were further contradicted by the intervention of the actress herself into the process of star image production. Certain stars, such as Katherine Hatburn, Marlene Dietrich and Greta Garbo, often asserted gestures and movements into their films that were inconsistent with, and even posed an ideological threat within the narrative. And the use of rumour and gossip about stars, especially by marginalised groups such as lesbians, further enabled different kinds of desire and identification to become focused on particular star images.

In the famous scene from 'Morocco', Amy Jolly (Marlene Dietrich), dressed in top hat and tails, kisses a woman in the cabaret audience, then takes her flower and gives it to a man, Gary Cooper. This flirtation with a woman only to give the flower to a man is a flirtation with the lesbian spectator as well, and a microcosm of the film's entire narrative trajectory. The film historian, Vito Russo, has written of this scene 'Dietrich's intentions are clearly heterosexual. The brief hint of lesbian she exhibits only serves to make her more exotic, to wet Gary Cooper's appetite for her and to further challenge his maleness.' But if we bring to the scene the privileged rumour of Dietrich's sexuality, we may read it differently as Dietrich momentarily stepping out of her role as femme fatale and acting out that rumoured sexuality on the screen.

Not only rumour, but also the scene's cinematic structure allowed for lesbian spectators to reject the preferred reading, as described by Vito Russo, in favour of a more satisfying homo erotic interpretation. Amy Jolly's performance, her singing a French song in Dietrich's inimitable voice and her slow, suave movements across the stage, is rendered in point-of-view shots intercut with two contending male characters. Yet when her song is finished and she steps over the railing, separating performer and audience, the image becomes a tableau. When Amy Jolly looks at the woman at the table, she quickly lowers her eyes to take in the entire body, to look her over. Amy Jolly then turns away and hesitates before looking again. The sexual impulses are strong in this gesture, impulses that are not diffused or choked by point of view or audience cutaway shots. Dietrich's gaze remains intact.

Furthermore, in the scene's conclusion in the giving of the flower to Tom Brown (Gary Cooper), she inverts the proper heterosexual order of seducer and seduced. Her costume, the tuxedo, is invested with power derived both from maleness and social class, a power which surpasses his, as represented by his uniform of a poor French legionnaire. While he is fixed in his class, she is able to transcend momentarily both class and gender. This fluidity and transcendence of limitations can be seductive for all viewers, male and female. For lesbian viewers, it was an invitation to read their own desires for transcendence into the image. Richard Dyer has pointed out, audiences cannot make media images mean anything they want to, but they can select from the complexity of the image, the meanings and feelings, the variations, inflections and contradictions that work for them.

Thank you.

- Andrea Weiss, A Queer Feeling When I Look At You: Hollywood stars and lesbian spectatorship in the 1930s in Christine Gledhill (eds), Stardom: Industry of Desire (1991) New York: Routledge

Misha MN reads Who's a Sissy? — homosexuality according to Tinseltown from Vito Russo’s The Celluloid Closet (1981)

My name is Misha MN and I will be reading from the 'Celluloid Closet', written by Vito Russell in the 80s, which is a book that studies the representation of homosexuality in early cinema; and there was a really good documentary of the same name that came out in the 90s, which I remember seeing as a teenager and it was very impactful. So I'm choosing to read parts of this chapter called 'Who's a Sissy?'.

Who's a Sissy?:

There's two things that got me puzzled

There's two things I just can't understand

That's a mannish actin’ woman

And a skipping, twisting woman actin’ man.

From Bessie Smith's 'Foolish Man Blues', 1927.

Nobody likes a sissy. That includes dykes faggots and feminists of both sexes. Even in a time of sexual revolution, when traditional roles are being examined and challenged every day, there is something about a man who acts like a woman that people find fundamentally distasteful. A 1979 New York Times feature on how some noted feminists were raising their male children revealed that most wanted their sons to grow up to be feminists — but real men, not sissies.

This chapter is concerned primarily with the genesis of the sissy and not the tomboy, because homosexual behaviour on screen as almost every other defined type of behaviour, has been cast in male terms. Homosexuality in the movies, whether overtly sexual or not, has always been seen in terms of what is or is not masculine. The defensive phrase "Who's a sissy?" Has been as much part of the American lexicon as "So's your old lady". After all, it is supposed to be an insult to call a man effeminate, for it means he is like a woman and therefore not as valuable as a real man. The popular definition of gayness is rooted in sexism. Weakness in men, rather than strength in women has consistently been seen as the connection between sex role behaviour and deviant sexuality. And while sissy men have always signalled a rank betrayal of the myth of male superiority, tomboy women have seemed to reinforce that myth and often have been indulged in their acting it out.

In celebrating maleness, the rendering invisible of all else has caused lesbianism to disappear behind a male vision of sex in general. The stigma of tomboy has been less than that of sissy, because lesbianism is never allowed to become a threatening reality any more than a female sexuality of other kinds. Queen Victoria informed that a certain woman was a lesbian, asked what a lesbian might be. When the term had been explained, she flatly refused to believe that such creatures even existed. Early laws against homosexuality referred only to acts between men. In England, the penalty for male homosexual acts was reduced from death to imprisonment in 1861. But the new law made no mention of lesbianism. Nor did the target of the pioneering German gay liberation movement, Paragraph 175, which outlawed homosexual acts between men but omitted any mention of lesbians.

The predominantly masculine character of the earliest cinema reflected an America that saw itself as a recently conquered wilderness. Actually, there was not much wilderness left in the early 20th century, but the movies endlessly recreated the struggles, the heroism and the romance of our pioneer spirit. There were Western movies, but no easterns; our European origins were considered tame and unworthy of the growing American legend. Men of action and strength were the embodiment of our culture, and a vast mythology was created to keep the dream in constant repair. Real men were strong, silent and ostentatiously unemotional. They acted quickly and never intellectualised. In short, they did not behave like women.

Unspeakable in the culture, the true nature of homosexuality haunted only the dim recesses of our celluloid consciousness. The idea that there was such a thing as a real man made the creation of the Sissy inevitable. Men who were perceived to be like women were simply mama's boys, reflections of an overabundance of female influence. It became the theme of scores of silent films to save the weakling youth and restore his manhood. Although at first there was no equation between sissyhood and actual homosexuality, the danger of gayness as the consequence of such behaviour lurked always in the background.

The idea of homosexuality first emerged on screen, then as an unseen danger, a reflection of our fears about the perils of tampering with male and female roles. Characters who were less than men or more than women had their first expression in the zany farce of mistaken identity and transvestite humour inherited from our oldest theatrical traditions. Rougher and broader than their classic predecessors, male and female impersonations, informed by a breezy vaudeville legacy, were a fascination of the movies from the beginning.

Many of the male and female impersonations of the American silent screen are stunning and of the finest comic creativity. The strident, vivacious foolishness of Fatty Arbuckle, John Bunny and Wallace Beery was the genesis of the Milton Berle school of drag humour, in which the joke lies in the very appearance of a man dressed up as a woman. But the subtlety and grace of others could at times capture the possibility of pure androgyny.

Early Sissies were yardsticks for measuring the virility of the men around them. In almost all American films, from comedies to romantic dramas, working class American men are portrayed as much more valuable and certainly much more virile than the rich effete dandies of Europe, who, in spite of their successes with women, are seen as essentially weak and helpless in a real man's world.

Webster defines Sissy as the opposite of male, and the jump from harmless Sissy characters to explicit reference to homosexuality was made well before sound arrived. The line between the effeminate and the real man was drawn routinely in every genre of American film, but comedies more often allowed the explicit leap to hope the homosexual possibilities inherent in such definitions. Indeed, the relationship between sissyhood and real homosexuality was born in the "anything can happen" jests of silent comedy. The outrageous nature of such films left a lot of room for nonsensical possibilities, and occasional real sexuality of a different nature would intrude as one of them, though it was never taken seriously as a realistic option.

Crucially at issue always was the connection between feminine behaviour and inferiority. The conclusive message was that quiet souls could be real men — but not if they displayed qualities that properly belonged to women.

The love that dared not speak its name in English was surprisingly fluent in German throughout the silent era. While America was using its new toy to play cowboys and Indians, recreating the fading dreams of its own mythology, European cinema was shaping the older lessons of life into a more realistic look at the battle of the sexes. In America, the battle of the sexes was Marie Dressler throwing dishes at Wallace Beery. In Europe, homosexuality was just another aspect in the panorama of human relationships. This has always been true. In 1956, theatrical producers had a lot of trouble producing Robert Anderson's play 'Tea and Sympathy' in France. A French producer told Anderson, "so the boy thinks he's a homosexual and the wife of the headmaster gives herself to him to prove he's not — but what is the problem, please?"

The acknowledgment of the Third Sex in Europe was apparently not bound up in a definition of masculinity as it was in America. The emotional qualities of the passions aroused in human relationships, rather than the sexual characteristics of such relations, was a focus of the drama and intrigue.

In 1926, New York Times critic Mordent Hall identified a few films based on the life of French sculptor Auguste Rodin and other prominent homosexuals took a shot at the subject matter. German producers delight in taking an occasional fling at France, England and Russia by filming stories dealing with historical characters who are not a credit to their respective countries. If producers were bent on delivering such a theme to the screen, it might have been vastly more to their advantage to picturize Oscar Wilde's story, The Picture of Dorian Grey, which, distasteful though it may be, at least possesses real dramatic value. Although Hall never mentions homosexuality in his review, he was the first in a long line of critics who were so blinded by the subject matter of homosexuality that they would review it with obvious distaste. It is apparent in Hall's choice of an alternative, ‘The Picture of Dorian Grey’, that a direct and uncritical approach to such unorthodox passions had unnerved him. He asked not for something with more dramatic value but for something with a strong sense of moral judgement. The homosexualizing of Rodin he considered an insult to France. Thus the 'theme' of homosexuality relegated these films to a level of sexploitation, and thus few Americans saw them.

This led to the use of the ‘harmless sissy’ image to present homosexuality. The sometimes silent connection between effeminate and homosexual was unmistakably evident here because, say, a gay cowboy looked not like a woman, but like any other cowboy in a film. The difference was that he preferred men — and therefore 'behaved' like a woman. The primping and fussing mannerisms of the cowboy actor were certainly woman identified, even though female impersonation was not a factor. Yet this was exactly the sort of thing the censors were watching for. Ordinances already empowered censorship bodies to look at films in advance of their public showing. And although such groups had no real clout at this time, their guidelines for morality in the movies specifically included 'sex perversion' as a don't.

The vision of two passionate women locked in a forbidden embrace was used by De Mille to condemn the excesses he was busy portraying so graphically. In return for his judgement on the 'crime', he was consistently allowed to paint a more explicit picture of evil, especially of sexual sins, than that was ordinarily permitted. This was particularly true when evil transpired in a biblical city. Quoting scripture on their title cards, De Mille's films became moral lessons rather than exploitation. They also became box office successes. Censors and critics did not buy religious convictions when Allah Nazimova presented Salome in 1923 with a reputedly all gay cast in tribute to Oscar Wilde, though in 1921 the censors had let slip a brief lesbian scene in her version of Camille. Salome was greeted with the kind of enthusiasm that is reserved for Off Off Broadway plays about Puerto Rican transvestites. In fact, the last time Salome had a major theatrical release in 1971, it was double-billed with Broken Goddesses, starring Andy Warhol's Puerto Rican trans superstar Holly Woodlawn. The sets and costume for Salome were taken from illustrations by Aubrey Beardsley and executed by Natasha Rambova, who was reportedly Nazimova's sometimes lover and the wife of Rudolph Valentino. The credit for direction given to Nazimova's husband, Charles Bryant, also belonged to Rambova, who wrote the screenplay under his name, Peter M. Winters. The film, a financial and critical failure, wiped out Nazimova's life savings and destroyed her artistic credibility for some time to come.

Nazimova, using her characters sensually and artfully as allusions to decadence and androgyny failed to condemn them. People found this offensive and repellent both visually and thematically. A later experimental film of a much higher order, James Watson and Melville Weber's Lot in Sodom in 1933, depicted the judgement and destruction of the biblical city in lurid and sometimes racist ways, but always fascinating terms. The film was welcomed grudgingly by highbrow critics on the basis of its innovative artistic merits, but its theme, hardly mentioned by most writers, was condemned by the few who spoke of it. According to Jack Babuscio, film critic of London's Gay News, the British critic Norman Wilson wrote in 1934, "it must be welcomed as an attempt at experiment, even though we deplore the choice of its theme and the decadent artiness of its treatment."

Both Salome and Lot in Sodom brilliantly executed exotically artificial milieus. But the costuming, the posturing and the highly stylized exaggeration were alien to the expectations of a broad general public, unable to find a frame of reference for the excesses in visual style that such films presented.

There were presages of 60s camp decadence, and it is ironic that Salome's revival should come with a similar effort by a Warhol superstar, for mainstream audiences tried as hard to pigeonhole the meanings of Warhol as they did Nazimova's artifice, again failing to enjoy their audacity. After exasperating an ABC television talk show host, Geraldo Rivera, in 1976, with a series of flip answers to his serious questions, Holly Woodlawn finally listened to his definitive plea. "Please answer me", Rivera begged at the close of his show. "What are you? Are you a woman trapped in a man's body? Are you a heterosexual? Are you a homosexual? A transvestite? A transsexual? What is the answer to the question?"

Woodlawn, who could have been answering Nazimova's critics as well, took a measured breath, looked at Rivera incredulously and dismissed his earnest concern with "But darling, what difference does it make as long as you look fabulous?"

Thank you.

- Vito Russo, Who's a Sissy? – homosexuality according to Tinseltown in The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies (1981) New York: Harper & Row

Hannah Regel reads Oliver Reed (2020), plus excerpts from My Lunches with Orson (2014)

I'm going to read a little bit from ‘Oliver Reed’, which is my poetry collection, and then some slightly newer stuff, but this will be short. And then I'm going to read from ‘My lunches with Orson’.

Oliver Reed:

There is a picture of you behind the bar where we eat French sausage and are drunk.

And I think I know since a child your huge hairy face, that I love you very purely, always have.

You smoulder in a mobile furnace.

One never thinks on the screen that there on the other side is an embryo, a living, lusting flesh being put out of play because you've got a mask on.

Oliver Reed, face of the old game birthed in the crotchet of rape.

I lift a little finger and taste the murgaz juice from my chin.

The simple life.

He said 'get over here', but first he grunted, a little erotic prickle that grunt.

Like a penis twitching in sleep, to get he said, where's your face?

And then put himself inside it.

As a child, that was how everything reached my mouth, from a love to please and impress.

Black olives, salted, anchovies, even snails once.

Isn't she curious? And now here you are.

The dear hunter.

In the brief time that I was pregnant, I watched everything related to Vietnam that I could find.

It's war.

All 17 and a half hours of the Ken Burns documentary: Platoon, Mashed, The Deer Hunter, Apocalypse Now, Full Metal Jacket, et cetera.

I was aroused and unfounded by the men, their rounded brown shoulders, quivering cigarettes, dusty noses.

I watched them all go to waste as I vomited into a mixing bowl on my second hand sofa.

I fantasised about being helicoptered into the fire, nipple tassels, swinging a sweetheart.

I would boost morale and in thanks be shown what sitting in a tank feels like.

My neck would be held in a firm but tender grip as I am shown how to move the gun, looking into the viewfinder.

"Like this, honey, here".

I would sit on their laps and they would be thankful for the economy and my soft body binding us forever in the humbling of sex.

How it makes religious animals of us all.

Swigging from the bottle we would sing soft hymns about this quick shot at living when we learnt how easy killing is.

I seem to have made so many mistakes.

When I was growing up my mother was really good, which is why no one lives with me.

Fashion first.

Even when I was young, I was into fashion.

Mum would show me patterns, I would tell her I wanted and she would do it for me.

I still cut amazing fashion, even now.

One day a winter will come and I'll throw my body like a watch.

The only piece of trash I've ever cradled sophisticatedly.

One day it'll be time to let it go.

Until then, I'll stay friendly.

I'll stay friendly and I'll say hi.

I'm in my tight clothes and I'm saying, hi.

That's genius right there.

That's acting.

So 'My lunches with Orson', I like, steal a lot of lines from it for 'Oliver Reed' It's based around these lunches between Orson Welles and Henry Jaglom, who's the director, and it's posited as this sort of privileged insight into the sort of inner workings of a great man's mind. But in actuality it's 300 pages of quite deluded ramblings. So, I'll read it.

'My lunches with Orson'

You didn't find him charming as hell?

No, no charm. To me, he was just a hateful, hateful man. Tracy hated me. He hated everybody. Once I picked him up in a London bar to take him to Notley Abbey, which was Lawrence Olivier and Vivien Leigh's place in the country. Everybody came up to me and asked for autographs and I didn't notice him at all. I was the third man, for God's sake. And he had white hair. What did he expect? And then he sat there at the table saying, everybody looks at you and nobody looks at me. But I don't think that's it, really. I think Katie doesn't like me. She doesn't like the way I look. Don't you know there's such a thing as physical dislike? If I don't like somebody's looks, I don't like them. Sardinians, for example, have stubby little fingers. Bosnians have short necks.

Orson, that's ridiculous.

Measure them.

I never could stand looking at Betty Davis. I hate Woody Allen. I've never understood why.

Have you met him?

Oh, yes. I can hardly bear him. He's the chaplain disease, that particular combination of arrogance and timidity, sets my teeth on edge. He's not arrogant. He's shy. He is arrogant. Like all people with timid personalities, his arrogance is unlimited. Anybody who speaks quietly and shrivels up in company is unbelievably arrogant. He acts right, but he's not. He's scared. He hates himself and he loves himself. A very tense situation. It's people like me who have to carry on and pretend to be modest.

Does he take himself very seriously?

Very seriously. I think his movies show it. To me it's the most embarrassing thing in the world, a man who presents himself at his worst to get laughs in order to free himself from his hangups. Everything he does is therapeutic.

That's why you don't like Bob Fosse?

I don't like that kind of therapeutic movie. I'm pretty Catholic in my tastes, but there are some things I can't stand. I love Woody Allen movies, and I can never get over what you said about Brando. It's that neck which is like a huge sausage, a shoe made of flesh. People say Brando isn't very bright. Most great actors aren't. Lawrence Olivier, I mean, is seriously very stupid. I believe intelligence is a handicap in an actor because it means you're not naturally emotive, but rather cerebral. The cerebral fellow can be a great actor, but it's harder. Performing artists, actors, and musicians are equally bright. I am fond of musicians, not singers. All singers think about is their throats. You go through 20 years of that and what have you got to say? They're prisoners of their throats.

So, singers at the bottom, actors at the top?

There are exceptions. Leo Slezak, father of Walter Slezak, the actor, made the best joke of all time. He was the greatest Wagnerian tenor of his era, and the king, the uncrowned king of Vienna. If you're a Wagnerian, you know that he enters the stage standing on a swan that floats on the river. He gets off, sings, and at the end of his last arya is supposed to get back on the swan and float off. But one night the swan just went off by itself. Before he could get on it, without missing a beat, he turned to the audience and ad-libbed what time does the next swan leave? How can these people have such charm without any intelligence? I've never understood that.

Swiftly Lazar enters.

I just wanted to say hello. You look wonderful.

I feel good. I am good.

Orson, See you Wednesday. You take care of yourself.

What do you think? I look badly?

No, you look great.

Lazar exits.

I don't like people who say, "take care of yourself." He hasn't changed in 30 years. He lives in a hotel, orders a whole lot of towels and when he goes from the bathroom to his bed, he lays down a path of towels so he doesn't have to walk on the carpets. He's that nuts about germs.

What if he wants to go to the closet?

He'll make another pass. I've seen it with my own eyes. What does he think he'll get through his feet? From the Ritz? Mania?

By the way, before I forget, I got your contract for 'two of a kind'. John Travolta and Olivia Newton are set, along with your favourite, Oliver Reed, playing the devil. They want you for the voice of God for two consecutive days. I love playing your agent. They said to me originally, what kind of price do you think would be right? And I said, if he does it all, he'll do it for the work, not the money. But of course, you can't make an insulting offer. And they said, well, we were thinking 10, 15. And I said, really? For the voice of God? Maybe you should get someone else. I don't even want to submit that to him. I don't think it's fair. Why don't you round it out at 25?

Well I, well, they called me and they said, when I want God, I'll call heaven.

What is it with Oliver Reed? That you like him so much? Weren't you stuck in Greece with him in some B movies?

A movie for which the money never arrived. It was a Henry Allen Towers production, 1974. Harry Allen Towers is a famous crook. He's a guy who was charged with running a vice ring out of a New York hotel in the 60s. Also being a Soviet, it worked for him for years. He always took the money and ran. He once fled Turan, leaving Oliver Reed with the hotel bill. Oliver went down to the nightclub at the Hilton, which is in the basement, and broke it up. All the mirrors, chandeliers. Wrecked the whole place, destroyed the whole nightclub. Everyone was in such awe of the violence that they all just stood back in horror, including the police. And he just walked out, went to the airport. Nobody ever laid a hand on him. I admire him greatly. Life affirming. I reject everything that is negative. I don't like Dostoevsky. Tolstoy is my writer, Gogol is my writer. I'm not Joyce guy. God knows he's not. Affirmative. No and that's why I don't like him.

But wait a minute Orson. What are you talking about? This a stupid conversation. Touch of Evil is not affirmative.

Listen, none of my reactions about art have anything to do with what I do. I am the exception.

Thank you.

- Hannah Regel, Oliver Reed (2020) London: Montez Press

- Peter Biskind (eds), My Lunches with Orson: Conversations Between Henry Jaglom and Orson Welles (2014) London: Picador

Hannah Regel is a writer based in London. From 2012–2019 she was the co-editor of the feminist art journal SALT. Her writing has been published in The Poetry Review, Fantastic Man, Granta, Canal and Noon, amongst others. She has published two collections of poetry, When I Was Alive and Oliver Reed (both Montez Press, 2017 and 2020).

Lauren John Joseph is an artist and writer, who works across video, text, and live performance. They have written extensively on contemporary culture, art, performance, pornography, gender theory and the Golden Age of Hollywood, contributing in print and online to publications including iD, The Independent, Sleek, The Guardian, Time Out, Attitude, Amuse, Siegessäule, Parterre de Rois, Charleston Press, and the ‘zines Birdsong, Fat Zine, 21st Century Queer Artists Identify Themselves, and Not Here: An Anthology of Queer Loneliness. Previous authored works include At Certain Points We Touch (Bloomsbury, 2022) and Everything Must Go (ITNA Press, 2014), and the plays, A Generous Lover and Boy in a Dress, which were published by Oberon in 2019.

Misha MN is an artist, poet, writer, photographer, performer, shaman, zine maker and queer culture curator, working between Brighton and London. They are a contributing editor for Polyester, surrealist showgirl for underground cabaret troupe Club Silencio and author of monthly column Culture Slut.

Sam Cottington is an artist and writer living between London and Frankfurt. He writes plays, performance, novellas and short stories; and makes painting, collage, sculpture, installation and video. Recent exhibitions and performances include: Civil Twilight, Ginny on Frederick, London (2022); Blanks, Ridley Road Project Space, London, UK (2022); Pennies From Heaven, London Performance Studios, London, UK (2022); Getting Dressed, V.O Curations, London, UK (2021); Crave, SET Lewisham, London, UK (2021); Haus Wien, Vienna, Austria (2021) and Deadhead Perfora, Yaby, Madrid, Spain (2020). His first novella People Person was published in 2022 by JOAN press.

Bette Davis and Joan Crawford during the making of What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962). Photo/ Archive Photos Getty Images.

Joan Crawford and Bette Davis in Whatever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962). Credit Rex Features.

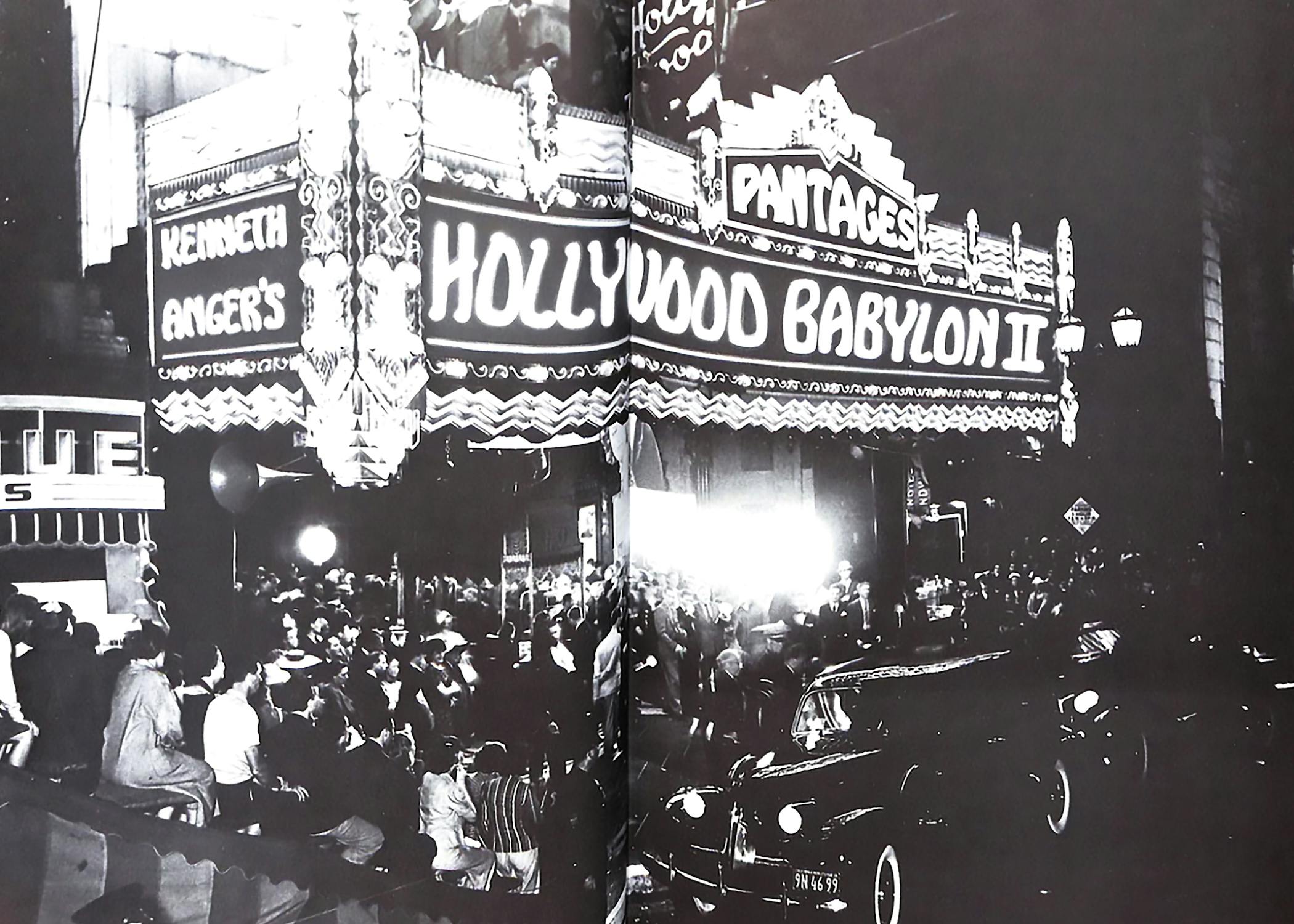

Kenneth Anger, Hollywood Babylon II (1984). Courtesy of EP Dutton Inc. New York.

Ramon Novarro, Francis X Bushman and Kathleen Key in Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1925). Credit Mgm Kobal Shutterstock.