Anthea Hamilton was nominated for the Turner Prize in 2016. Large-scale solo exhibitions have included The Squash at Tate Britain (2018), Anthea Hamilton Reimagines Kettle’s Yard at The Hepworth Wakefield (2016) and Lichen! Libido! Chastity! at the SculptureCenter in New York (2015).

Anthea Hamilton and Nicholas Cullinan

Frieze Masters Podcast

In January 2023, Anthea Hamilton joined Nicholas Cullinan on the Frieze Masters Podcast to discuss the trajectory of Hamilton’s work, the roots of her identity as a ‘Londoner’ and how what she terms the ‘fourth dimension’ shapes her practice. Presented in partnership with Studio Voltaire.

Read the full interview transcript

Nathan Clements-Gillespie:

Hello and welcome to Frieze masters talks. I’m Nathan Clements-Gillespie, director of Frieze Masters, and I’m delighted to introduce this talk of Studio Voltaire with artist Anthea Hamilton, renowned for her surreal installations and performances. You can find more talks on the series at Frieze.com.

Nicholas Cullinan:

Thank you so much, thanks for the very kind introduction. Thank you for being here at the end of this very busy week. So, Anthea and I are going to be in conversation for about forty-five minutes, and then Anthea has very kindly offered to take any questions that you may have. So, if you want to think about that during the talk and then we’ll throw it over to the floor. So Anthea, I just want to say, it’s really a privilege for me to be in conversation with you. I have been an admirer of your work for some time so this was a really exciting opportunity to be able to have a conversation about it.

Rather than go through your entire career, we’ll weave through some themes, but I wanted to begin... And oversee the images rolling behind us of Anthea’s work over the last few years, but I thought it might be nice to begin with this week. Obviously the stand that you curated for Thomas Dane gallery, at the Frieze Art Fair, won the best stand prize. And I think there are some very interesting motifs, so I wonder if you wanted to begin by talking a little bit about the stand and what you did.

Anthea Hamilton:

Yeah, sure! I think I wanted to add also that you kindly jumped in at pretty short notice, maybe 24 hours, maybe less. Because it was just like a… through no fault at all, but I think a number of the people that had been invited initially to be in conversation - for whatever reason - every single one of those people was no longer able to make it. And I thought it was interesting because it all kind of represents different facets of my practice. And so, it would have been a really different conversation with each of those people, and I find it interesting that here I find myself with you, the director of an institution. And thinking about my work, often somehow has begun to make a lot of sense within institutions, as well. So it’s been interesting to then, to have to find a way to present work in an art fair (it’s one of my least favourite spaces, I must say).

But I was invited by the gallery, Thomas Dane, based in London and Naples, to think about doing that. I wasn’t really sure why, in a way, because I was aware it was a very big risk for them to… you know. It’s obviously a very important time for them to be present in dialogue with the people they work with, that they have relationships with. But I also thought it would give me an insight there. My practice is very visual but I think I’m very much about digging into the archives of things and trying to find hidden internal structures of organisations, of institutions, of an artistic movement, of a fashion style… it’s actually quite like an excavation, which I’m always interested in. And so, I asked and they kindly granted me permission to look through the full inventory, which almost gives you a sense of an autobiography of a gallery: who they’ve worked with, when do they stop working with that person, what do they do with that person now, who might be missing, who could I bring into the conversation as well…

I was kind of like a kid in a candy store. There were so many artists that for me, that’s why I wanted to work with them. But then, it was a chance to show their work, so Jean-Luc Moulène, Lynda Benglis, Magdalene Odundo, there were so many people that were exciting to show alongside, but also I was aware it was an opportunity to open up the dialogue about bringing different artists in. So I thought about trying to work with artists just a little bit ahead of me, people who haven’t had the support that I’ve had as an artist. I reached out to Rita Keegan, to Nancy Willis and to Mumtaz Karimjee, all kind of working mid-eighties, whose practices, as commonly happens, have just been overlooked, they have not been supported. Rita maybe a little bit more, but the others have not had that space to do that, so it was to implant that within the support structure of the Frieze booth too.

Nicholas Cullinan:

And that is one of the languages of your work, which is research driven and specially looking at the recent past and excavating histories, which maybe have been forgotten about or become marginal.

Anthea Hamilton:

Yeah, yeah. But I think I haven’t really got… I think I’m missing some key inputs somehow. I’ve always managed to not really understand some ideas and hierarchies that might exist. I’m completely oblivious to those which I think is very freeing. Like I don’t really hold certain things as, not necessarily in terms of high culture or low culture, but in terms of power. I’m interested in not paying attention to that, or understanding how I might be subject to that, too, and then using the work to process those things. And I’m always trying to be sensitive of… when maybe thinking about… I think that for a while I had a big interest in disco culture, or maybe in the ideas taken from historical places, but how my reframing of those, would understand the risk of appropriation in that as well. I think it’s littered all the way throughout the practice.

Nicholas Cullinan:

I wanted to ask you more about that, there’s a few themes that we can draw out. Also just thinking about here and now, the events of this week, and the stand of Frieze Art Fair, but of course there’s a particular reason why we’re here at Studio Voltaire. One of the reasons is that you have a studio here, but also, when it reopened last year you did this extraordinary garden, and I wonder if you can talk a little bit about that as well. And the importance of context and site in your work.

Anthea Hamilton:

Hmm, that’s a big broad question. I think…

Nicholas Cullinan:

The importance of South London?

Anthea Hamilton:

The importance of South London… I was born here! I can’t get away from here somehow. I tried to claw my way out of the A23 but it keeps kicking me back. But yeah I think there’s a geo-political specificity to why I’m here. My parents both emigrated from their respective countries and this is where their communities were, and that’s why I’m here. Historically they come from Christian countries due to colonisation so I went to a Catholic school which gives you a whole heap of stuff to deal with growing up, you know. I definitely hold a lot of that psychological way of processing the world. And I think my parents, growing up in rural communities meant that this idea of self-sufficiency or gardening was very important, so it was something that was always happening around me, in the back garden, something that I completely rejected to run off to be an artist, kind of, twenty-odd years ago. And so I think what I find interesting is there’s always these practical, pragmatic reasons why certain things happen, and when I was invited to think about the garden - being a studio user here already and seeing the past life of the garden, there was this skeleton of an old raspberry bush that people would take fruit from, and you could see there was a sense of needing that comfort and I wanted to kind of bring that back, just in a renewed way, in a more framed way. So I was quite resistant - I think I do it in a lot of my work - to refrain from trying to push certain things back. So, I didn’t want to talk to a landscaper, I didn’t want to make a garden which performs, in a way. I think a lot of the garden spaces that I go to are about the performativity of plants rather than just the functional use of it.

Everything in that garden is edible, in one way or another, whether it’s the leaf, the root, the fruit that it makes. But I am still completely drawn by beauty and materials as well, so it was significant that that functionality is framed within … I don’t know, I love to look at all those pebbles, I love to think about that charred bench that’s there, so it’s a kind of bringing together of things. Always.

Nicholas Cullinan:

And obviously that sort of raises the importance of the organic material in your work, and certain motifs, whether it’s lichen for example, and this kind of mix of the animal, vegetable, mineral which I find very interesting. Could we talk a bit more about that? The other thing that I would like to get into is the motif of the squash, which is adjacent to the organic but obviously in your work is transformed. But if we start with the literal use of organic material in these kinds of contexts and assemblages.

Anthea Hamilton:

I think that came from me just trying to be difficult when it came in, I think I’d heard a Duchamp quote that a work of art was no longer the same thing twenty years later because the materials themselves had changed. And I think I ran with that. I was like yeah, let’s speed up that process and can the work re-exist a day later. There’s a lot of arte povera artists working with organics, is it Giovanni Anselmo who makes that incredible work with the lettuce and the rock kind of tied together, and you need the lettuce to be fresh otherwise the whole thing just falls apart.

Nicholas Cullinan:

And actually that’s interesting, I did my PhD on Arte Povera, so yeah, the Anselmo piece which is these two granite blocks with the lettuce sandwiched between them, it only kind of remains a sculpture if the lettuce is fresh and as it wilts, which it will within a few hours, the block would fall, so it has to kind of be constantly fed. But there’s also, like, I mean, thinking about your work, I was thinking you know of for example Jonas Conelas installation with live horses breaking down this barrier between sculpture and also the performative which I think you do very much too.

Anthea Hamilton:

I think I like that there’s things that introduce tension, whether it’s the literal tension of torque or a piece of string or if it’s the difficulty that entails because it requires that kind of repeated stewardship of a work, whether it’s the idea of me looking for things in the market which you could get in a supermarket here in the UK but then it suddenly becomes completely impossible in Antwerp. There’s this tension which comes up in using traditional - what do you say - non-traditional art materials. For me, I think my practice is always just reframing what’s around me, and those things are not always museological, they’re just the materials that I have, that I’m in direct contact with. I think I’ve always wanted… I’ve always just really enjoyed touching things, you know, that was my first memory was, like, the touch of some carpet somewhere, and I think I’m still completely driven by that sensual effect of something… yeah.

Nicholas Cullinan:

And that’s so interesting because I suppose there is this tension in your work between the scopic, like the visual and how you frame installations for example even here, at Frieze with this tartan grid which we can talk more about - so between the scopic but also the haptic, the way that you set materials, I mean even thinking about the garden here, the contrast in materiality between the vegetable and the tiles, you know those sort of hard, shiny… And it reminds me, and I was sort of very intrigued to read about this, when I was swotting up this morning on your work, which is about this kind of tension between reconciling the two-dimensional image and the three-dimensional image. Could you talk more about that, like scopic/haptic, but also 2 and 3D.

Anthea Hamilton:

Hmm… Everything with me is like a thesis, it’s a bit tricky to go in, but I think I’m seeing my practice as learning, there’s a couple of ways I can think about this. So I studied - I trained as a painter. First I was on a fine art course and I thought I want to learn about screen, I want to be a filmmaker, I want to think about how we can make images that can exist within that space, and so the first thing I thought of that I felt like I needed to teach myself was how to make an image so I was interested in how things were arranged within painting, especially -

Nicholas Cullinan:

And perspective, I guess, as well, which is very much part of your work, I mean just seeing the images scrolling behind us there’s always this sense of perspective.

Anthea Hamilton:

Yeah but I think I was also very interested in a different opportunity for perspectives that you would see maybe in Japanese imagery and also Chinese imagery where things aren’t necessarily that two point perspective but could be orthogonal or could be circular, and that there’s other rules for making things, and other opportunities for different dialogues, that one shouldn’t dominate the other, and maybe I think the thing that is significant in my practice is that we’re often looking at it from a point of the West or from London so it seems maybe more one way than it is somehow. But I think it’s also, I just struggle with too many factors, so I think I have to make things flat, like the idea of making something three-dimensional kind of blows my mind completely. Like I can’t drive because I can’t understand what happens at the back of the car…

Nicholas Cullinan:

But you make things that are flat, or that follow a kind of very linear perspective, like for example the boots which we should talk more about, but they seem to be almost activated and given agency in a three-dimensional realm by your use of installation. So it’s this kind of tension between it’s a two-dimensional image but it’s almost turned into an object by its environment or its setting in a way.

Anthea Hamilton:

Yeah maybe that’s a kind of empathy I have for objects, is that they’re quite subject to being viewed maybe quite unsympathetically, or there’s a sense of the neediness of a viewer, whether that be me but normally I’m thinking of an audience in that way … And so, I think a lot about the positioning of things, so I guess that’s three-dimensional, but it’s very much about how to make those objects or images the best that they can possibly be, or the most supported I can make them within a three-dimensional space. I’m aware of the impatience of the viewer… yeah I think I was going to add another thing, but I think that’s all okay.

Nicholas Cullinan:

You mentioned the viewer, and I want to talk more about the exhibition in Antwerp that I was lucky enough to see earlier this year, but I mean to lead into that, it seems to me that obviously collaboration is fundamental to your work, in many ways, but it feels like also everything is a collaboration with the viewer as well. That the work is only activated or even completed, or made to live, by the viewer. Is that something that you think about? When you were… I mean I’m just thinking about some of these installations, it feels like they require the viewer’s presence, and their vantage point in a way to actually be made to work.

Anthea Hamilton:

I’m not sure it is, I’m not sure it’s true, actually. I think I see everything as material, like in a sculptural way, so an institution is material, like its physical materiality and the surfaces of it, or all of the bureaucracy and stuff, that’s material too because it’s definitely thick and hard to work with.

Nicholas Cullinan:

It definitely is, I can vouch for that.

Anthea Hamilton:

And so I’m interested in those senses of, all the visible and non-visible aspects of art-making, and maybe that’s why I could make a kind of flat-ish or extruded sculpture because everything else is incredibly complicated and that’s enough, that’s something to do with it already, but then in terms of … The viewer is just another thing, you know, they’re not less or more, they’re just another thing which has to happen in that way. And I think the thing that I wanted to add about the idea of the two-dimension was that something can only be two-dimensional because it exists in a three-dimensional space. And so, this idea of three-dimensionality - this is where I go kind of beyond myself - because we’re actually functioning in a four-dimensional space. And I try to think of what might be in the fourth dimension, if it’s not just depth, and for me, those fourth-dimensional things are emotions, power, wealth, and those are the kind of things which I think are shaping the practice as I kind of go forward as well, like the kind of non-material aspects of things.

Nicholas Cullinan:

You’ve mentioned Antwerp which was your first survey to date, I suppose we could call it, and you’ve also mentioned the kind of institutional context and how that feels and how it relates to your work or not, and I just wondered if you could talk a little bit about that project.

Anthea Hamilton:

Hmm, I don’t know what to say, I’m still recovering. Something I think is maybe key is nearly every image we’re seeing here is done in the last twelve months, so it’s been like a very intense year of making, and I guess there was this idea of reviewing oneself, and I think I’ve always been someone in a very forward-facing, never look back, keep going, so it was interesting having to come back and reframe that, because I’ve always worked in a very site-specific way, you know really thinking about the terms and conditions especially in a project like the squash at the Tate Duveens which was very much made for that quite local institution whereas here, with the collection that they have there, knowing how the behaviour of the audience in the Tate in a very kind of British context, how do you then translate or filter that to Belgium? Which is not a space that I’m that familiar with. And then also thinking about the physical, the visual references of the work are all of them known.

There was one that was in the work for a really long time, and the curator was like, ‘ah I really think we should have it in’ and I was like ‘yeah me too’ and she said ‘yeah because you know it’s this person’ and I was like ‘that’s not who it is’! And we spent the whole time both thinking it was really important to have this person in that actually we had completely different references to. And then as soon as that became clear, it was like okay, that one’s going out because in fact it’s not, I don’t know, culturally dominant enough to kind of function in this space. But I think, this idea of … I think I’ve often worked in spaces which are very much in the round, or even though they’re three-dimensional there’s a flatness to them. So, if you go into the Schinkel Pavilion or if you go into Thomas Dane, if you go into the Tate there’s always this sense of being able to have the whole image at once.

Nicholas Cullinan:

It’s almost like a scene, isn’t it, almost like stage-sets, that you’re - I mean not to put the viewer in again but you’re almost guided or even dictated from one particular point.

Anthea Hamilton:

Yeah, and I think that’s this idea of implied rightness, which exists within those spaces, I’ve often kind of played with. So to kind of suddenly be in a space which feels very long, very awkward, lots of strange angles, lots of very, like, other priorities in terms of how that space was built. So I think it was significant that it was up on the first floor, you would kind of go and feel quite trapped in there. I also of course made the show during the pandemic so I couldn’t go and really familiarise myself with the kind of quality of how that space was within the city and within the institution as well. And so I think it became quite a mental exercise, really, it became quite non-visual, very much so, but always thinking about how to process that through the idea that people would be standing in front of it.

Nicholas Cullinan:

And I guess, to you, how to have like a survey that doesn’t morph into becoming a retrospective or sort of put all your work together in a linear way, I thought it wove together all of your motifs, which I want to talk more about, really beautifully without it being kind of linear or chronological or literal.

Anthea Hamilton:

But I think that’s something which is kind of inbuilt into the practice, because, again, not thinking one thing better or more important than another, or realising that some works within my practice have a lot of … get around a lot? But other things are less known. I think there was a really key work in the show which was a work that I made when I was nineteen on my BA, and I was like this work has to be in the show, this is my best work ever.

Nicholas Cullinan:

Which work was it?

Anthea Hamilton:

It was a video work called Over the Rainbow, and I just thought somehow that’s like the kernel of all the other works that I’ve ever done, and it’s important for me to declare that. Or I don’t think I’m reaching some kind of mastery of what I’m doing either. Often when you see a show, yeah, it’s chronological, it’s like this is the moment, and now it’s all good, it’s all … or it’s all in dialogue with one another, as well.

Nicholas Cullinan:

I think now is a good time to ask you about some of the individual motifs, because of course they are sort of woven through your work, and they repeat. They are constantly changing depending on the context of the work, but I think it would be good to just really drill down into some of them, and talk a bit more about them individually. We can begin, I mean, with any of them but one I wanted to begin with was the squash, which has also obviously been the title of the Duveen 2018 Tate Britain installation. And also, and you can see it in the images behind us, the way that that takes the guise as a kind of sculpture but also as costume and performance. Could you talk more about that?

Anthea Hamilton: About squash the show, or the squash, a squash?

Nicholas Cullinan:

About squashes?

Anthea Hamilton:

Squashes. I think I like that it’s, how would you say, like a noun and a verb? Yeah and I definitely felt it as like the verb, quite often, more than anything else. Which maybe, if I jump back into thinking about like organic material, again, what can I say about that? … I really like the idea of abundance, in a way, or the idea of, I think I always grew up with food being really celebrated, this idea of a feast, like you could just have as much as you want, like there’s a sense of like total and sensual enjoyment within eating, and that you would never question that. I think I had a few experiences as a child when you realise that’s not how things are done, that’s it’s actually quite a family-based thing, that it wasn’t about knives and forks, that it was about whatever, stuffing one’s face, in an excellent way.

Nicholas Cullinan:

Or you could eat buffet.

Anthea Hamilton:

Yeah, or you can eat buffet, and that being like excellent, with no doubt about it. Or I think to tie in with this idea of being able to touch things within work, that for me I think I’ve always tried to put things in the work that we know what it’s like to handle them or to hold them. But then the squash itself, now we can see it up on the screen, I think when I was offered the commission I thought I would want to just use something really selfish, I’m just going to do something for myself in a way. Like it came not long after the Turner Prize which was very much about delivering towards the prize itself. So I thought that in a way that performers I’d say they are pretty much like a proxy for me, somehow. And with that you think what do you, what do I want? What do I want to be? And they were giving me this big corridor, what am I going to do with it, and I thought well, let’s invite some other people to be in here, they just need to look really good, if they’re going to be just walked past, if they’re going to be ignored, if they’re going to be misunderstood, so let’s reach out to the person I know with the best capacity to support me, and I had a relationship already with Jonathon Anderson who’s the creative director of Loewe, and I was like could you help me make these guys look amazing and he said yes. So that’s something that exists in that already. And then everything else was just kind of a - if you were a vegetable, who was a human, who was other, what do you need to survive in that space? Yeah, you need a hot costume, you need space. I don’t want them to touch that floor that exists in the Tate already, I find it completely dark-side, they need to be in their own universe, they need to take as many breaks as they want to take, they need to be paid properly, they need to have other sculptures, like Henry Moores' and stuff, just in case people want to look at those instead, so it was just really quite practical in a way.

Nicholas Cullinan:

So the whole thing was really designed around the performers' needs in a way I guess?

Anthea Hamilton:

Absolutely, I worked very closely with a movement director, Delphine Gaborit, who, a lot of it in a way was about how to deal with the audience, and if they want…and when we did the audition process, anybody who was kind of like, ‘wow this space is amazing’ we were like, ‘you’re out’, like this is not it, this is for you. Like anything you need from us, we are gonna make sure we try and provide it for you, like this is… you’re not here to perform for anybody. I always want a better term than ‘performers’ in fact, that they were not doing that. So the movement was very much… I mean quite often I think people were just sleeping in there. Which was a lot, I felt like we got somewhere good if you can ask, if you can get people to have a sleep in the middle of the Duveen's, in a non-performative way.

Nicholas Cullinan:

I mean that's actually an important point, you’re right. It’s not about performance or performers. Obviously one of the key references of your work has also been, you know, theatre, especially of the 60s and 70s, and in fact actually the ‘illiteral’ guise of the squash actually comes from that.. I was wondering if you could talk a bit more about that?

Anthea Hamilton:

I think the history of that image for me, still, there's still lots to be uncovered with that. I had found that image in a book while I was studying at the RCA on a painting course, and it spoke to me. You know, it’s a very kind of open image, its beautiful, it shows the kind of squash character in a repose, lying down slightly, the angle slightly tilted down so you have a sense of the squash kind of coming up from the ground towards you, and I think, then every studio visit I would have with a fellow artist, curator, whoever, I’d be like, ‘look at this! I could do something with this!’ and it never quite took, but it was never - no one ever kind of said, ‘I kind of recognise that’ or … It was just quite unknown. You know, based in the UK, it’s quite an unknown image. Um, many years, coming back to the Duveens, I think we was like, yeah, that’s it, we have this image, movement was coming from it, in terms of the movement for performers, very freely, we all went ahead, it opened, and then suddenly another kind of facet of what the image, the history of the image, came forward. And in fact it came from an Eric Hawkins, dance performer, Eric Hakins was a choreographer who was working in the 60s actually, the former wife of Martha Graham, and the piece, the costume was taken, the form of the costume, is based on a Hopi Kachina, of the squash, which is something I think is significant that in the UK we have no knowledge or we’re not given any. That sense of Indigenous American cultures is completely cut off from us. Because I think when I would often try to dig or go back to the library and find it, it was like dead ends every single time. And so whilst I feel quite uncomfortable that maybe I was like, could be guilty of like cultural appropriation, which exists elsewhere in the work but in a very knowing, kind of biting way -

Nicholas Cullinan:

- With the kimonos or kabuki theatre?

Anthea Hamilton:

yeah, then, this could have been a clumsiness. Yeah, and I still think about that, like when it came to reworking this work, it's about letting people know that there’s… that that exists within the work also.

Nicholas Cullinan:

I like also how you use references sometimes in a very deliberately kind of casual way. Perfect example - John Travolta, that's what I was going to mention, and you obviously mention that the relationship with disco was - I was reading where you talked about how Travolta for you was almost just like a found object, you don’t care about him he’s just a kind of… well this is my word and maybe it’s not right, but maybe a cipher, just an image to explore?

Anthea Hamilton:

I think that’s how things like that have often existed in the work, so I think Travolta, who’s been there for a while, I think that he’s in the work as a flag to represent disco culture, but disco culture that, how can I say it now, that disco culture that was only coming up in the 1960s and 70s, in New York, then it was built in the kind of, the queer Latin communities, like you know, people, like poor communities and suddenly there was technology and suddenly you could have like a whole orchestra at your fingertips, if you wanted, or you could just have some amazing sounds, or you could suddenly do everything, what you want, and this kind of wilful sense of growth, what would you call it… like this incredible capacity for making suddenly was offered. And people, and then you know, that coming through as a process of defiance or just you know, excellence coming through. And then suddenly you know, that's kind of spotted as having some creative capital and it gets commercialised and it gets turned into Saturday Night Fever with John Travolta as the star of that, and it’s become a corruption and it’s become something else, and the image of that face which I find to be classically beautiful, almost like a roman sculpture, becomes like a screen that kind of holds back and no longer gives opportunities to those communities, and so he’s pretty much there to stay behind all of this, behind this one singular image is everything else that has been blocked off from us.

Nicholas Cullinan:

That's true, I mean in a way he is a sort of poster boy for cultural appropriation.

Anthea Hamilton:

Yeah within the practice I think moving on from one motif to another, that's how the kimonos operate too - that it’s not me thinking ‘wow they’re so cool they're super nice I love that’ yeah it's a really totally an object I do not understand, I have no accurate access to it, like the ways in which I've learnt about it are construction based here, and I think the kimono that I’m quoting, is born from like coming up from like the belle epoch, there was a moment when that was really interesting to the west, or suddenly it was accessible and it was seen as the chicest thing.

Nicholas Cullinan:

You’d see them in things like, for example I think it’s Manet and Renoir, the paintings from the 19th century, of western women wearing kimonos.

Anthea Hamilton:

Absolutely and I think it’s like that idea when something takes currency and becomes, suddenly it's speaking all of the right languages, and it's probably to do with trade or other things or silk routes or a changing government that's allowing that to come forward. Um, you just have this beautiful garment that can like bare the weight of all of it and that has consistently done so since then, and I think all of the ones in which I've made, are there for me to then throw my image at it, and its a, something that doesn't break, it's a very strong cultural object in that way.

Nicholas Cullinan:

The other motif which runs throughout you work, which is kind of at the other end of the spectrum which I want to ask you about, is the kind of grid, whether it's the rectangle linear kind of hard grid of tiles that we see here, which you obviously use as you mentioned for the 2018 Tate Britain installation, and also the use of tartan, I wonder if you could talk a bit about those two particular types of grid, but I suppose also like the grid in general, as opposed to the more organic, messy matter that you use, so the tension between the kind of orderliness of the grid, and the rationality and the linear nature, versus the more organic that's there at the same time.

Anthea Hamilton:

I think the answer would kind of depend on how I was feeling on the day, maybe today I would say that I just like need that support, like I just need a bit of structure, and it's also the simplest way to just get myself that structure through a straight line, um, the garden outside, that's another kind of linear space, but I was aware that it needed to have the hand in it too, and so the gate is actually made in collaboration with - I invited my partner Nicholas Byrne to do that, because he can actually deal with that complexity, he can, he’s a much more like - I don’t know, three dimensional thinker, but I think with me I like the idea of the modular, that you could have one thing, and I could look at it in the studio, like get that right tile and then just let it go, it's like an endless scroll.

Nicholas Cullinan:

- and repeat

Anthea Hamilton:

Yeah, and so that's very much how the grid works in the series of works which is to do with either the squash or very early works also using tiles, I like that they are cheap materials too, but you can really elevate them, if you're a good enough tiler you can make them look incredible. So I think this thing that's always stayed with me, like a belief and the beauty of a material, just looking at it long enough to get it to kind of tweak the way it can be, I find amazing.

Nicholas Cullinan:

And then the tartan, which is kind of adjacent to that - this is right on queue it's perfect - could you talk more about that.

Anthea Hamilton:

Yeah so this tartan, it first came into the work in 2018 or so, so the subsequent show to the squash was The New Life, which was at the Secession in Vienna, it was a dream place to do a show, also they’d just had a renovation, the floor was spotless, and I was thinking about my works going in there and they just weren't holding up, and so I decided to do something almost like a big graffiti tag all over the space and just put the Hamilton clan tartan all over the floor, but then kind of knowing that having a Caribbean father that that name has kind of been attached to my family one way or another, I've tried to track back, I can't quite find out why, but it's imprecise why it's there, and so for a while I was interested in always using the Hamilton tartan, and in the metal black and grey monochrome room that we see, that's kind of been slanted so in a way it’s tartan under geological pressure, then I was just like wow if it’s just a tartan then just go for it and then I think I just really enjoy how all those patterns work you know, and also - I need to recheck this - but I think a lot of tartans we just made up and sold to Americans looking for their heritage in a way and so yeah it’s just like if this is a fabrication, so why not just enjoy it, and so now, at the Thomas Dane booth there’s a Menzis tartan in Calphallon Repetto, there is a Glenfruin and something else, and just putting them together it’s becoming like a Comme des Garçons shirt and I’m enjoying that.

Nicholas Cullinan: - I mean it is a whole industry, I can speak to that for like Americans of like Celtic descent, which is me, they're incredibly obsessed with finding their clan tartan or family tartan in a way that I don't think Celtic people from Scotland or other places are…like as bothered? But for Americans there’s all these different ways you can find your ‘clan’ and your tartan, it's a whole industry.

Anthea Hamilton: Yeah but I think I just like what the lines do also, you know, or maybe that's it, I guess you just have check patterns in lots of different cultures also, it's something that just exists because it’s just about the warp and a weave of fabric, that's just what fabric tends to do as long as you start to dye them. I enjoy that, or almost just - of course it helps to give resonance to other things that happen in the space, like how to lay out a work, whether this ties in with the architecture or is awkward and doesn't fit with that, yeah they're just quite enjoyable to work with.

Nicholas Cullinan: And actually this too, I was wondering if you could talk about this particular project which obviously secured your nomination for the Turner Prize, and this is the iteration in the Turner Prize, I suppose the reference to Gaetano Pesce and architecture.

Anthea Hamilton: Um I think, during one of my deep library dives, around 2005, 2006, a came across a work, a monograph of Gaetano Pesce’s work and in with the other kind of Italian radical designers, his work really spoke to me because it's kind of the most enjoyable use of materials I'd ever seen, like forget all of that sculpture that I had been close to when I was studying, materials were the purpose or materials applied like an attitude which I found very refreshing. So he would make a series of chairs that were just like casts but maybe some of the casts would fail but that was your set of six chairs for your dining table, whether one has come out or not. There was this will of like it's the idea that counts and the materials supporting that happening I found really enjoyable. And then Project for a Door, I mean it speaks to a lot of the things that happen in the work, I mean it’s large scale, it’s the body, it’s humorous, it’s provocative, it’s gendered, it’s doing a lot of things which I would use as ways of measuring how a work would work.

Nicholas Cullinan: And just to say, so his original project which you remake, and I want to ask you about that idea as well about that word, was done if I understand it for an upper east side house, it's quite subversive in a way?

Anthea Hamilton: Yeah, so I think the reason why he made it to be so was silicone was a new material at the time and I think the companies were kind of dishing out to everybody ‘have a see what you can do’ and Gaetano’s response was that, so he cast the ass of a notable architect in silicone rubber with the cheeks spread and said ‘this is your house’, New York’s meant to be a very radical city but in fact can you deal with it? Or can you not? No of course nobody’s going to have that - or it wouldn't be allowed - this idea of obscenity, um it's pretty small actually what is permitted and so it was really like yeah you know sticking your finger up to whoever it was and I think I like that it was all about that sense of provocation so then when I was invited in 2014 to have the show at the Sculpture Centre, which is a very big space, the curator Ruba Katrib was like, ‘do you want to do something big?’ and I was like… I've got something that we could do. And um, I was thinking about this last week, that we never would’ve made that work first off in the UK, there's such a different sense of humour or titillation, how silly art can be here, that I think would have shut down the reading, the thinking and the conversation around that, but it's great to be able to do things in different places because you can have a different dialogue. In New York they've seen everything you know, that's nothing, walking down the street you’ll see 10,000 things wilder than you know a big ass… yeah.

Nicholas Cullinan: - I’m aware of time because I want to have time for questions, I'm sure there’s questions from the audience, you said the the Gaetono Pesce homage reference was originally made for New York, for the Sculpture Centre, then you revisited it for the Turner Prize in London, was there a very big difference between the audience’s responses to it? I'm just curious if Britain were a bit more, I’ll speak for myself, maybe a bit puerile, school-boy humour, but I don't know, did you find a very different response?

Anthea Hamilton:

Slightly yeah, slightly. I think also that the context of the Turner Prize, for that to happen is it also amps that up somewhat… so I'm glad it was seen elsewhere first. But I think, interesting why it was important for me when I restaged that work, to not only offer that, to not only show the Sculpture Centre show, but the space was kind of bisected and on one side you had the sculpture centre and on the other side it was like there's another part of Hamilton that’s here and this is something else we look at, and then I think it kind of changed the… I don't know, like if you were at a mixing table it kind of changed the qualities of how that object was seen. It wasn't seen as a one and only you know it was seen as part of a dialogue of making, and I often don't know what people see, I can imagine the big pumpkins in the fair, that's seen as what my work was, or in the garden here, ‘oh we saw you made the cauliflower fountain’ like no, I did everything, like the whole thing is there, and I've thought about it in the round, and I recognise that

Nicholas Cullinan:

And it’s what is between, not just the things themselves, I mean there's so much more to ask but I'm aware of time - time for questions… if there are any questions do you want to raise your hand?

Audience member: Hello, there seems to be lots of really quite ambitious works that we’ve seen today. That being said, do you have anything that you can let us into that you plan for the future that might be as ambitious or as exciting as what we’ve seen?

Anthea Hamilton:

I'm going to have some time off… (audience laugh) but that’s really hard isn't it, that's really ambitious I think, that as a sole trader, that as an artist that you can actually take some time off and that your career might be waiting for you when you decide to come back to it? That's something that I feel is quite a gamble, I'm probably only going to take 6 months off or something but that feels, that's definitely new for me. Otherwise, one of the things I'm working on… definitely I'm working on some kind of stage play? I don't know what that is, which I think will be really difficult for me actually because I've been so much about the audience being a physical three-dimensional material, so what happens when they're definitely at a distance? And I think, I hope I've been able to support my performers by knowing how people behave in proximity to them… but what happens when they do become you know absolute spectacle... I'm not too sure, because I'm always very specific about who I want to work with, and why as well, and I don't want to make them vulnerable within that, so I think that will take quite a lot of extra thinking through.

Audience member 2: Hi, um, it's a silly question but I was wondering if you, because of the slowness of plant growth, even though it it's a lot faster than what - inaudible - said … and some of their motifs and the 2D thing, if you think about it in terms of, or if you think about still life? Whether that's a useful notion?

Anthea Hamilton:

That is a good question, there was an image I took out that I normally show at the beginning of every talk that I do, which is by Cotán, which is an incredible still life and its… I should know… ‘quince, melon, cabbage, pear’? I got it wrong, but it's a still life actually arranged to show the exponential rate of decay and another time rate also, and so maybe, I guess you say still life is like the first painting that I saw, not necessarily in a museum, but you could see it on a tea towel or you’d see it on a tray, and on the stuff around your house, so I guess that's like my first access to painting in a way, so the painting for me was already mediated elsewhere… so it was quite a given? In a way… but then I think about the kind of rigour of the composition in the Cotán painting a lot, and always apply that. I think these first works that I did were a lot about balancing or assemblage, or the weight of things, or I don't know… the temperature of things as well. I think all of that is still very much present, at the moment in quite a metal phase, haha, that sounds more interesting… not like heavy metal, yeah, just galvanised metal, yes just I really think about how cold it is and how amazing that is in reaction to the body also, which I guess I tied because of the way heat would transfer into that object as well, yeah.

Nicholas Cullinan:

Can I just follow up on that because I think the still life idea is really interesting and I suppose coming from a portrait gallery I was struck reading that you think of some of your works as almost like self portraits, so there's even this element of genre there as well, potentially… like still life, but sort of portraiture as well?

Anthea Hamilton:

Yeah and in funny ways they are, because, in a way I get a bit confused, because maybe we could say that these giant pumpkins are somehow self portraits but then you would put the performer on the top that's also a self portrait, then you would have the floor that's also a self portrait. There's something that Rita Keegan said just, to me a couple of weeks ago that ‘you've always got yourself, and if anything, you've only ever got yourself’ and I think …I'm the first viewer of my work as it's being made, and so I'm aware that it's full of all of my values, and I think in a way, your personality is actually all of your coping mechanisms and your experiences mixed together so…maybe that's why it's nice that I would collaborate often, cause it's a sense of not be yourself for a minute, but then you kind of draw it in also and you become hybrid as well.. Yeah see, I don't know what I am as a person so it's nice to be able to have these kinds of external manifestations also yeah.

Audience member: I have a question… I was wondering how you perceive different senses when you propose your work. I know you’ve touched on touch but in previous works you also incorporated smell? Do you mind elaborating a little more on that?

Anthea Hamilton: Yeah I think one thing I wanted to bring with me which I didn't, but I've made an incense with a young scent designer called Ezra Lloyd Jackson which is also another self portrait. And actually I don't have a very good nose, at all, so that one's a bit of a mystery but I like the idea of all the non-visual things, because I'm aware that the work is very visual, so it's important that you… that there's all these other spaces left open to the body and I think the olfactive is quite exciting in that way, I think the first time I had done it I did a performance at the Serpentine which was also kind of the first manifestation of the squash, it was called Grasses, and I worked with two performers that I’ve worked with a lot, so often, as well as, not that the people I work with are motifs but I keep coming back to like very familiar spaces all the time, unfolding and unpacking them each time a bit like how a grid would work, it's this complex and simple thing at the same time. And with those performers, I was aware that maybe they could be seen in a certain way, or not judged on their own terms so I made them a perfume that they were doused in and at the time they both had long dreadlocks, so everytime they would sweep round this kind of beautiful smell based on secrets and a walk in the grass would swish past everybody. And it's the kind of thing that, you know, you it's maybe just a detail at the moment…I know that there are other artists who their main kind of focus is working in scent, and for me it still just about making sure we don't take what we see for granted, it’s kind of about undoing that, or opening up another potential of an image, the behaviour of an image as well.

Nicholas Cullinan: Thank you, I think that might be it. I have to say it's been such a wonderful conversation. I just want to thank you so much for talking about your work in such an eloquent and fascinating way. So please join me in thanking Anthea Hamilton, thank you.

Previously Curator of International Modern Art at Tate Modern (2007-2013), he worked on exhibitions such as Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs (2014), Malevich (2014), and Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye (2012), and was involved with many aspects of the second phase of the Tate Modern project, for which the new building, designed by Herzog & De Meuron, opened in 2016.

Prior to joining Tate, he was the 2006-7 Hilla Rebay International Fellow between the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, Venice. Previous experience includes in 2006 a Helena Rubinstein Internship at the Photography Department of the Museum of Modern Art, New York and Lecturer in Art History at the University of Wales Institute, Cardiff from 2003-2004.

Exploring themes of identity, originality, geopolitics and Blackness through a historical lens, the new Frieze Masters Podcast is now available. Bringing together some of today’s most celebrated artists, art historians and curators, the podcast launches with the Talks programme from the 2022 edition of Frieze Masters – one of the world’s leading art fairs – and offers compelling insight into the influence of historical art on contemporary perspectives and creativity. Subscribe now on Spotify and Apple Podcasts.

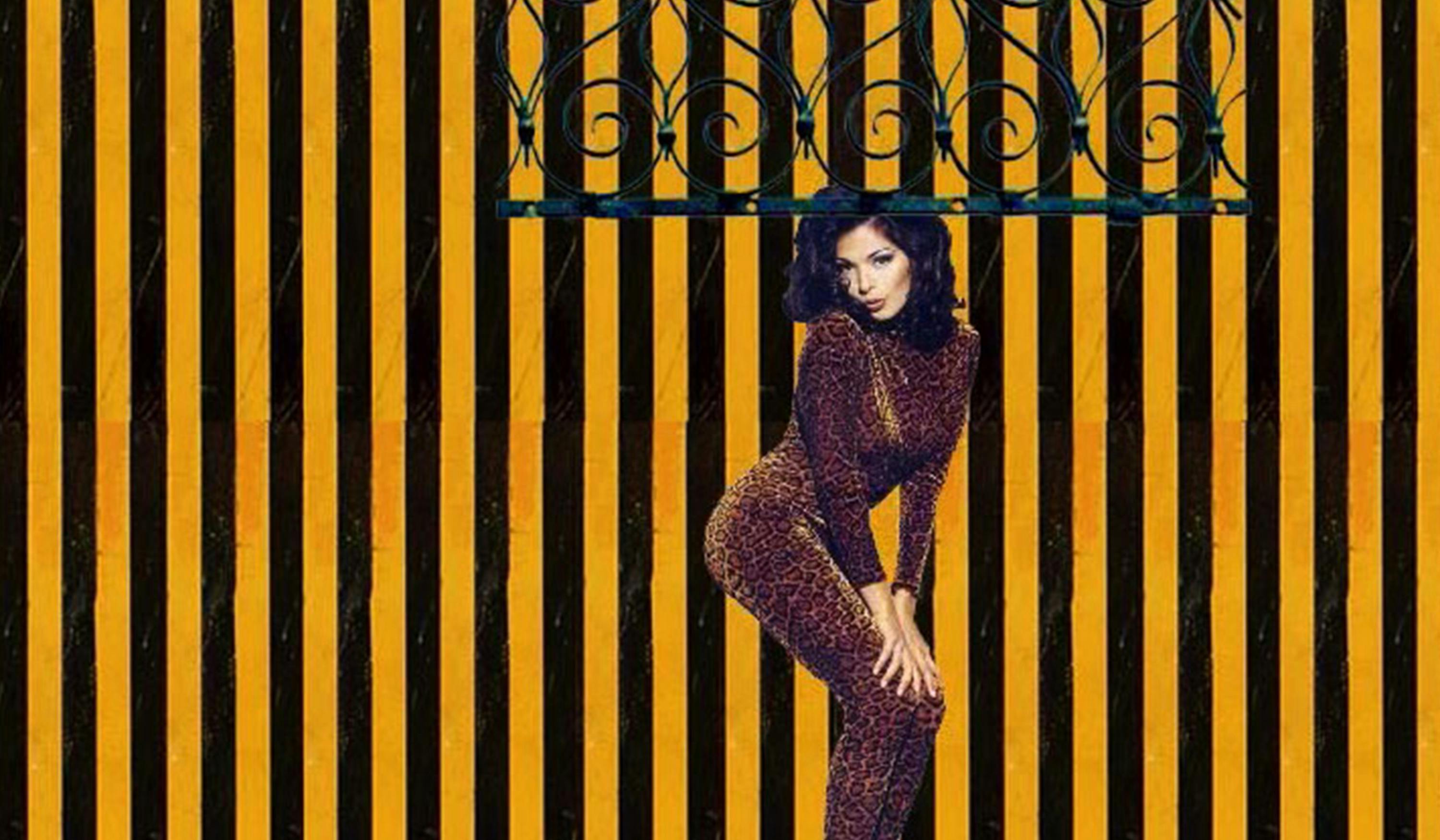

Anthea Hamilton, Mash Up, 2022, installation view. Courtesy: the artist and Thomas Dane Gallery, with special thanks to LOEWE; photograph: Kristien Daem / M HKA Antwerp.