Nathalie Olah is an author with an interest in class and propaganda. Her books include Bad Taste (Dialogue Books, 2023) an exploration of the intersection between consumerism, class, desire and power; Sarah Lucas: Happy Gas (Tate Publishing, 2023) and Steal As Much As You Can (Repeater Books, 2019). Her writing has been published widely in periodicals including ArtReview, The Guardian, Tribune, Jacobin and The Times Literary Supplement.

Saturday Talks Series: Nathalie Olah

Writer Nathalie Olah led a talk in response to the art of Beryl Cook.

Situating Cook in the British mid-century, Olah explores the artist’s work in relation to the academic interests of that time — namely pop-culture as a relatively new phenomenon, and the spread of American soft power through its entertainment machine. With reference to writers and theorists including, Richard Hoggart and Stuart Hall, Olah offers a re-reading of Cook’s practice.

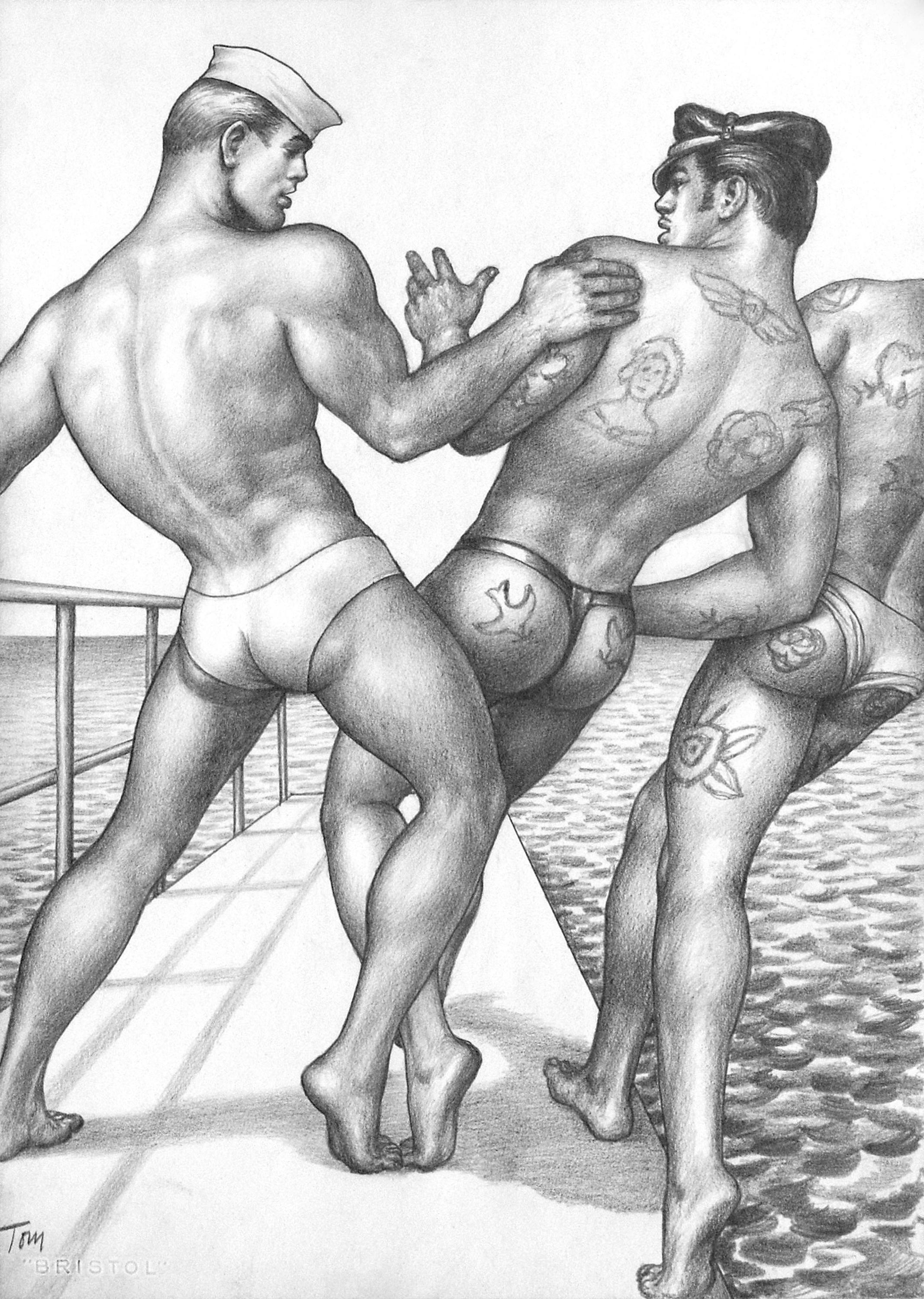

This event was formed as part of our Saturday Talks series, in which artists, curators and writers lead personal responses to Beryl Cook / Tom of Finland.

Contributors include Lauren J. Joseph, Tai Shani, Luke Turner, Nathalie Olah, Emily Pope and John Edwards (of The Backstreet).

These talks, readings and performances were an opportunity to explore specific aspects of the exhibition, from 'bad taste' to class tourism, masculinity and sexuality in the military, and London's lost queer spaces.

Nathalie Olah Transcript:

Nathalie Olah: Thank you for coming. I have to apologise. I've got quite bad allergies, so I'm a little bit congested, which might stifle my ability to raise my voice, but I'll try to be as clear and as loud as possible. I also feel like what I'm about to do is maybe a little bit fun police. It's not, I don't think, because the real fun is what we get from correctly contextualising an artist’s work. I’m joking. I don't actually agree with that, but in the case of Beryl Cook, I think it’s useful because it’s never really been done. I’m going to start with something that might seem a bit counterintuitive, maybe a bit pretentious, and that’s bring up this idea of the aura, and the definition of that word put forward in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (1935) by Walter Benjamin. I’m not being facetious by bringing this up in relation to Beryl Cook. Part of the point of this talk is to point out that somebody like her really illustrates what Benjamin was talking about.

In that essay, Benjamin considers what is lost when the likeness of an artwork, a photograph, or a print, is recreated endlessly and disseminated via mass production models. The aura is a quality that can only really be accessed by being in the physical presence of the original, and arguably only increases the closer we are to the original scenario in which it was created. It's the evidence of craftsmanship, it's seeing how something was made, but it's also having an awareness of the material conditions in which it was created and the social forces that it was responding to. Even those who advocate separating an artwork from questions of authorship, would never go so far as to wrench it from its material and historical reality. For example, there's no appreciation of Leonardo da Vinci that doesn't include an awareness of the fact that he was using oil paint in a new way and responding and somewhat subverting the more glossy, empirical styles of the other Renaissance artists — doing something quite interesting and exciting with light.

None of which is really inferred or you're able to understand from seeing the Mona Lisa printed on the side of a mug or a tote bag. That's something that you gain from being in the presence of it, from having some understanding of the time in which it was made and of the context. When you see that image or a reproduction you understand that it is important: you might even be able to have an emotional response that says it's beautiful. But its significance remains somewhat elusive and mysterious without a little bit of that contextual understanding. Now, despite all of us in this room probably having seen an image of the Mona Lisa long before we saw it in person — if we did ever see it in person — we still also had an understanding of it, that it was a real painting that existed somewhere. We all knew that this image had a real life that predated its existence on the side of a tote bag or on a mug or on a calendar, or whatever it might be.

I'm not sure that is something that we did all appreciate or know about someone like Beryl Cook.

I'm just thinking back to my first encounters with her. Without ever consciously thinking about it, because I didn’t know about such categories, I think I probably had her images down as some kind of illustration, or graphic design. I certainly didn't stop to ever consider that these images I knew from their oversized limbs and smiling faces were physical paintings that had been rendered in oil, that there was a depth to the colour of them that is very evident when you walk into this room and see them in person, or that there was so much skill and appreciation for form that had gone into their creation. All of which sounds very serious and maybe slightly out of place but I am trying to stress this point, that as an artist who most of us only ever considered through a mass production gaze, the charisma of finally seeing them in the flesh for the first time is all the more great and impressive. There’s an aura, for sure.

But what does it mean to be a practitioner who existed primarily as a reproduction and is only now being considered an artist? It's a peculiarly modern phenomenon. She was only disseminated and brought to us in that form because of technological developments that took place in the mid-century. So cheap colour printing, manufacturing that harnessed petrochemicals, transformed into plastic.

I think I have been asked to speak here today because I recently wrote a book about taste and how it relates to ideas of class and consumerism and politics. So yes, casting my mind back, trying to remember my first encounters with Beryl Cook, like I said, I probably did see her work on mugs and calendars and all the rest of it. But there is one moment that I can locate her specifically. It was in a department store that I used to regularly visit on a weekend, which had a sort of art section. And what I remember seeing was Beryl Cook reproductions; and Jack Vettriano, reproductions. I don't know if anyone remembers him? That was slightly more nouveau riche. It was often couples dancing, always on a wet beach, and there were normally butlers with umbrellas to protect their hair. There was also Anne Geddes. I don't know if anyone remembers Anne Geddes? I can't quite figure out who her fan base was… She used to turn babies into flowers, put them into flower pots? Ok, so I remember there being Jack Vettriano, Anne Geddes, and then Beryl Cook. I think Beryl was generally associated with an audience or consumer that was quite comfortable with themselves and with their social and economic standing. A consumer who was just looking to have a laugh. I remember seeing prints of Beryl being sold alongside these other images. Though I had some tacit understanding that this is what people considered to be art, long before I'd ever set foot in a gallery or anything, I also knew that none of them were taken particularly seriously — and couldn't have been if they were stashed next to the cuddly toy and discounted cookware section.

So my first instinct on writing a book about taste was to rail against the idea of bad taste, which I had always felt was basically a legitimate way of perpetuating certain forms of classism and racial discrimination. With Beryl Cook, sitting firmly in the bad taste camp with respect to art, my instinct is the same. It's the same desire to shout about how these works are valid for the simple fact that people love them. But, the truth is that I don't necessarily believe that. I don't necessarily believe that because something is popular and beloved of people, it necessarily deserves critical acclaim. I don't think Beryl even needs critical acclaim. Nor do I think that Beryl needs me to come and jump to her defence and start arguing the case for why she's valid and should be taken seriously. I think it's a little bit patronising.

So, I don't just want to offer a reactionary reading that says, “Justice for Beryl. She's been maligned for too long, humiliated by the art establishment, et cetera”. What I want to do is situate her in a critical tradition and to highlight the false assumptions that existed in people's scepticism towards her. If we're going to extend generosity to Beryl and give her the reappraisal and critical attention that she lacked in her lifetime, then I believe we should also extend the same generosity to her critics who were also only responding to the world that they knew and the conditions that they were familiar with. I make a distinction here between those who might not have liked Beryl's work, but on its own merit, and were worried perhaps, about its departure from more self-serious traditions in British art; and those who were reactionary and simply affronted by a lower middle-class woman who painted fun, joyful scenes from everyday life. I've written a review of this show for ArtReview, and it's primarily about that. It's about the fact that Beryl was, undoubtedly, on the receiving end of unfair prejudices. But giving some credence to the people that might have been a bit scared by, like I say, her departure from these more self-serious strains in British art, I just want to say that not all of her naysayers were bigots.

I think it is very important to situate Beryl in post-war Plymouth, as this show is very eager to do. If you go and read any of the captions or any of the material in those cases, Plymouth is a big theme and a focus of this exhibition. Plymouth had been bombed extensively in World War II. There was the ‘Plymouth Blitz’. There were a thousand fatalities, and there was a huge mass migration out of the city. This was because it held certain strategic advantages in war. It was a naval base. Warships and submarines frequently arrived, docked, and departed. But it had also been integral to the Empire, and its wealth, prior to World War II, was a result of its global merchant trading abilities. In this sense, Plymouth exists as a great microcosm for transformations that were taking place in British society after 1945. It was a society that was undergoing a period of contrition and humiliation. There was an economic recession and a need to rebuild. But more abstractly, there was an existential problem of what Britain might be in an age of decolonisation, in which its de facto power had been considerably diminished.

Beryl’s husband was in the Merchant Navy. She travelled with him to Zimbabwe in 1956. They returned to Cornwall in 1965, and they moved to Plymouth in 1968, at the point when the city was rapidly starting to change. There had been a huge effort to rebuild the city after the war and after its destruction. In the 1950s, they were building 1,000 new homes a year. By 1964, there were 20,000 new homes in Plymouth, which completely transformed its tapestry. It went from being a densely populated, very small city in which there was a lot of poverty, to being a much more diffuse suburban sprawl, with a city centre that was freed up for consumerism, shopping, leisure, and some of the things that you see around you in these paintings. Also, that city centre was reimagined in a new modernist, futuristic sense. So it was also a place that I think would have felt very exciting. In a moment, I’m going to talk about a writer called Richard Hoggart, who wrote about this time, specifically looking at the north of Britain. I think one thing that I always neglect to think about when considering this moment in history is the fact that a lot of people living in cities would have, up until a couple of years before, been in the sticks. They were living in very rural places that had no access to a wider culture beyond what was available in the village hall or in the local shop. So it's hugely transformative. People are moving into cities, and these cities are, because of other bigger forces, which I'll also talk about, becoming part of this big global network, and they're in dialogue with other cultures. That's creating fascinating and exciting, but also intimidating and frightening possibilities in the minds of these people that aren't necessarily used to these new encounters.

The Plymouth that Beryl would have encountered then was something like an experiment, and her arrival occurred at a time when Britain was seeking to resolve its existential problem by building deeper and deeper ties with America. It was at this point that British society really submitted to the spread and growth of American cultural hegemony and soft power. On the one hand, a product of globalisation that facilitated a positive move towards things like IGOs that were created after World War II that encouraged greater interstate cooperation and dialogue. It allowed for things like the civil rights movements and sexual liberation and women's rights to spread across the Western world, all of which is obviously a great positive development. But globalisation also meant global financial systems that were unmoored from resources and localised needs. Britain's power would increasingly come through its proximity to the great cultural hegemon, and it would wield its influence through attracting service-based businesses. This is also the time that we start to see a real boom in mass-produced goods and their consumption; and Art and literature actually wouldn't be spared from that phenomenon.

Like I said, Beryl produced her first painting in 1960. Three years earlier, Richard Hoggart published his seminal study, The Uses of Literacy (1957). Now, this is a caveat. I write in the tradition of cultural studies, and this person, Richard Hoggart, is very influential to me. I don't know that he ever came into contact with Beryl Cook's work. There's no evidence that he did. But I still think that his work, which was to analyse how the cultural tapestry of Britain was changing under the influence of these forces from America, is relevant here. He created the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at Birmingham University, along with Stuart Hall, and they had their slightly different takes on that discourse between British and American society and culture. The Uses of Literacy, observed how books, in particular, were being transformed under this mass market tendency. Going back to Benjamin's theory of the aura, Hoggart lamented the fact that because of mass production, commissioning standards were also being degraded as these disciplines prioritised the cheap and sellable over any other measure of worth. He was sad about the fact that essentially this was happening in literature, and the tradition of high literary art was being lost in favour of Mills & Boon. Now, we'll all have different takes on that. Hoggart is frequently accused of being a snob. But I think his point holds that literacy is always celebrated as a great thing, as a net positive. But if it's actually only being used to consume the Daily Mail, is that necessarily, I don't mean this in a snobby way, but if it's a Daily Mail that's peddling an Islamophobic line, is literacy necessarily a good thing? It's more a philosophical question than an aspersion or class-based judgement. These are extreme arguments, but they illustrate a point that there was this creeping sense that American cultural hegemony and its tendency to commodify absolutely everything, while providing a short-term answer to the existential dread that was felt by Britain at the time, could also be transforming society for the worse.

Beryl is an artist who does not shy away from these transformations. I think this is where some of the confusion around her work might have happened, because I think there was maybe a mistake in the mind of, for example, the Director of the Tate Modern in the 1970s who said that Beryl Cook would never feature in their collection and would never be displayed in the Tate Modern, in which they thought the fact that she dealt in this subject matter necessarily meant that she was endorsing these wider cultural changes. I think reading her work is much more complicated than that, which is what I'm about to go into.

We often hear that she is a painter of the working or the lower middle class in Britain. While it's true, it's only half the story. On closer inspection, she is a great chronicler of the strange interactions that occurred between a relatively parochial British culture that was rapidly disappearing, and a new, shiny, globalised culture that was encroaching. Like I say, there are two sides to this. On the one hand, this dialogue meant there was a big opening up of travel and influence beyond the white, culturally conservative culture that had existed in Britain for so long. I think much of what you see in terms of the celebration in these scenes is about that. It's about the fact that this is finally dying out, this prurient, overly judgemental, curtain twitchy tendency that was British society, towards something that was far more liberal, open, expressive, and accepting of different people and different ideas. She celebrates sexual liberation. She participates in it even. She was a great lover of lingerie, apparently, which I learned yesterday. There's a picture set in one of these cases here of a woman who's wearing a BDSM set with exposed nipples, and she's got a whip, and apparently, Beryl owned that set. She was a great fan of all of that. She loves queer spaces. She warmly observes the discomfort felt by the suited business class, whose urges are suppressed until night falls and the beer is flowing. She clearly associates America, to an extent, with that sexual awakening and women's liberation. There’s a portrait here of a woman — I'm really sorry, I've completely forgotten her name…

Speaker 2: Barbara Ker-Seymer.

Nathalie Olah: Barbara Ker-Seymer, who was...

Speaker 2: She was a photographer and was a part of a lesbian group which was well known throughout Paris, New York and London, who were just doing great things of art. They were seen as the bright young stars who were going to see through the next century. She did amazing stuff for both lesbian fashion, but also lesbian art throughout the century.

Nathalie Olah: I think this portrait is so lovely. Ker-Seymer and her lover. It's a very quintessential New York scene. I would recommend going and having a long old stare at that one when you get a chance. There's also something very interesting about taste in her work. Leopard print is everywhere. My own book is leopard print. Why was leopard print synonymous with sexuality and deviance, but also a disregard for the puritanical tendencies of Western culture? I don't know, and I really do need to look into this, I don't actually know where leopard print in particular comes from. But what I do know from writing my book on taste is that what we tend to associate with good taste has its origins in colonialism. It arrives from the Protestant forms of Christianity that were imported into America, primarily in the form of Calvinism, which was extreme in its austerity and its minimalism. This then became the visual language of the American imperial project. You might have heard of WASPs. It means white Anglo-Saxon Protestant. Their whole style is understated and demure.

It meant that the baroque tendency of Southern European countries, which then colonised much of the Global South, by virtue of finally being defeated and having been dominated by the American super hegemony, became to the Western gaze, at least, the visual language of the trashy. So your preference for Italianate overabundance becomes a form of rebellion and an act of defiance against that ultra-conservative, tightly-controlled, central power within the American imperial project. There is a painting over here called The Lady of Marseille (c.1990). Marseille I must say, is a place that has always resisted the more extreme forms of white Western imperialism and has been a home to many across the Mediterranean, including North Africa, as you probably all know. It is a painting that defies pretty much all expectations of womanly virtue in the more contemporary Western tradition. Yellow, potentially like self-tanned skin, sturdy thighs, big exposed ass, leopard print, a preference for small dogs over men…

So on the one hand, we have this great sexual liberation happening in Plymouth and its suburbs, and the people of Plymouth have a whole range of responses from the excitable and the giggly, which I think are really sweet. I mean, you can see it in the stripper over there. Apparently, again, I can't take credit for this, but Kitty told me a wonderful story about that painting…

Speaker 2: So Beryl really wanted to go and see Ivor Dickie. She wanted to see what the male striptease was really all about. But once she got there, she couldn't stop staring at all the women's faces. They were just too funny for her, so she ended up making them the main thing in her painting instead.

Nathalie Olah: There's the full gamut of expressions there: the awkward, trying to look away; the face of a woman who is absolutely relishing it, can't get enough; or the face of the woman who just can't stop laughing. There is this sense that these people have never seen this before, it's completely new to them. The people of Plymouth are starting to feel themselves. They are starting to have the audacity to play with their hair and their makeup. For women in particular, there's a possibility of becoming something other than the domestic servants of their mother's generation. In many of these paintings, such as Hairbells (2003), I noticed that the faces are all eerily similar. You start to think that maybe these aren't even real female subjects, in the sense that there's something quite archetypal about their faces and the fact that they all have similar makeup looks. There's something quite interesting in this because we tend to think of women's liberation as being about the full acknowledgement of our subjectivity: being taken seriously in our own right as individuals. But here is a form of liberation that is slightly different, where we want to achieve ‘the look’. And ‘the look’ in the first instance is emancipatory before the cogs of the advertising machine get whirring. There's a very sympathetic instinct, of wanting to be somebody else, and there's these things that will allow you to do that. I think she captured that really perfectly. It's this attempt for these women, a wholesale phenomenon of women deciding that they're going to cast aside the roles of the past and assume a new role for themselves.

The problem with all these observations is divorcing the exciting first flourish from the way in which capitalism then swoops in and aggressively commodifies. All these paintings capture that first initial sense of excitement, which was born of globalisation and this dialogue between cultures before, metaphorically speaking, the moment that the big corporation comes in and starts trying to sell it in a really aggressive way to people. They are dreamscapes, and they might annoy some people for the way that they gloss over the material reality that I just mentioned, but they capture an essential experience and a paradox at the heart of working-class and lower-middle-class life, which is the want for that freedom without it having to necessarily come at the cost of the planet or other people. Too often we castigate the urge. That urge for expression, for joy, for leisure, for wanting to be seen in a new way, for being vain, for wanting to take pride in our appearances, with the forces that pray on it. Beryl provides a valuable lesson in that sense. There is nothing cynical or sad about any of these scenes. Actually, that first instinct is very beautiful. That interface between tradition and the new that creates possibilities for people also allows them to consider possible alternative ways of living. Beryl may have been slightly idealistic, but what she's not is fawning or apologising for the aggressive forms of marketisation that followed, in a way that I think many of her critics might have assumed that she was. She is not endorsing the cheap and the mass-produced. She's occupying that moment, that libidinal moment before the question of how the stuff is actually made and sold comes into play.

If we look at Elvira's Cafe (1997), we can see that collision between worlds. You have the homemade and the hyper local, (like cakes, baked goods, tourism leaflets for local attractions that have heritage signage on them), but we also see beyond them, the rows and rows of identical canned goods and produce. We see this hench form of modernity in the shape of a naval officer. His back is to us and he's anonymous. It's a symbol of the outside world, of this cosmopolitan society coming into contact with this much more parochial space. This, I think, is what Beryl was capturing. I think this is what she did better than anyone else, and it's how we should view her, as opposed to just a straightforward chronicler of working-class and lower-middle-class life. I think that collision between cultures is essentially grasping what she was doing. The works then take on a whole different appearance and a whole new life. Because there is a tendency to see things only from a contemporary perspective, to think that these scenes constitute working-class life in a plain and simple way without understanding the peculiarity that is only a product of understanding their context. These things are just so common and so normal to us now that we do just take them to be shorthand for working-class or lower-middle-class life, but actually, at that time, they constituted something novel.

This tension between a world that Beryl remembered and the one that was being ushered in in the 1960s never leaves her. Even as she moved beyond that time into the '80s, the '90s, 2000s, it's a preoccupation that persists. Shoes are a big thing: they're identikit, but they're also glamorous. They're bought on the high street, but they're emblematic of freedom, and they seem to never escape her notice. Even in the very, very late paintings, there's these, yes, quite generic shoes that take centre stage. She seems fixated with shoes.

The irony is that Beryl of course becomes the mass production model herself, not that she deliberately engineered things in that way and who can blame her for going where the opportunities occurred. But from almost the beginning of her career she gets unmoored from all of this stuff — her surroundings. In that way she was reduced inaccurately to a two-dimensional emblem for a tendency that people were rightly concerned about, but which they had no right directing at Beryl herself. The comedian Victoria Wood described Beryl's works as ‘paintings, but with jokes’. I might be paraphrasing that, sorry, but I think that was the quotation. Anyway, I think they are a lot more than that. They were observant of a new interplay between cultures, one that produced moments of excitement, but also scepticism and irony, awkwardness, prudishness, titillation, embarrassment, shame, and hilarity, towards forces and tendencies and which we are now so used to, which have become such a part of tapestry of contemporary British life, that we almost don't see them.

So, thank you to Studio Voltaire for allowing us to redress that blindness and for giving us a chance to see the world through Beryl's eyes.

Beryl Cook, Big Shoes, 2006. Image courtesy of the Beryl Cook Estate.