Luke Turner Transcript:

Thanks to everyone at Studio Voltaire for having me. Thanks to you all for coming. I was really interested in Studio Voltaire for asking for quite a personal response, because I'm actually not an art critic, I'm a music critic. So it's quite interesting getting to look through the work and feel how I responded to it through the prism of the life of quite fluid sexuality. I love that you've got a very queer artist paired together with Beryl Cook — there's a lot of ambiguity, a lot of horniness, and that's the sort of space that I like to exist in, so this is a sort of exploration of that. A couple of notes, there's quite a lot of sexual references: a reference to abuse and a few things like that, just to warn people ahead of time. But thanks a lot for coming along.

Beryl Cook, Tom of Finland & The Horny Complexity of the Bisexual Gaze.

Cindy Crawford glowed through the musty gloom of my teenage bedroom in a gold swimsuit, the supermodel’s skin goosebumped and covered in droplets of oil or water, unzipped at the front, nipples hard, the material cut so high up on the thigh that I’d get as close as I possibly could to see if I could work out where she’d shaved her pubes. Next to her was Guns & Roses guitarist Slash, shirtless, tidily muscled, leaning back, with his guitar as gold as Cindy’s swimsuit swung away to reveal a treasure trail of hair wiggling its way down to the crotch of his leather trousers, laced tightly over the bulge of his cock. Yet it’s not just creases in leather trousers that connect that poster to the works Tom of Finland and Beryl Cook, and teenage me to today, but the layers of meaning I might unpeel by opening them.

Aged 13 or 14, these two posters on my teenage bedroom were formative for my emerging fluid sexuality. At the time, I had little culturally to fall back on to understand this, no support network, few icons in the public eye. This was compounded by growing up in a strict Christian environment which, though loving, made me feel like a sinner. These posters might have been quite vanilla, but looking back I realise that the public juxtaposition of my taboo desires was an act of rebellion, a secret code hiding in plain sight.

I am a firm believer that when something is repressed, it takes on mutant, potent forms. Confining a fluid sexuality just leads to it raging ever more strongly within ourselves, and then overflowing in unruly ways. I wonder if this is where the bisexual’s reputation for hypersexuality often comes from. We appear, or are, or sometimes might be, hornier than other people because we exist in a state of denial that forces us to constantly consider which way our desire is slipping next. Our identity becomes focussed on the sexual act, and the parts of the bodies of any gender through which those moments of liberated selfhood might be found.

So I found my way into my sexuality through looking, seeking, wanting to touch. I put the posters up innocently enough – GNFNR were my favourite band, I loved watching Baywatch on the telly, for the wild swimming – but the feelings they sparked in me developed into a stronger voyeuristic urge. From the posters I got my kicks by flicking through the mens and womens underwear sections of the Kays mail order catalogue, before graduating to mid-90s hedge treasure jazz mags (Razzle, Readers Wives, Club, the men of the far rarer Playgirl and hens teeth Vulcan or Inches). When the internet arrived with my 18th birthday, this eventually led to a difficult addiction to online pornography and webcams. At the same time, I quickly graduated into an ambiguous enthusiasm for exhibitionistic sex in cruising areas, saunas and so on. I sought to define my loose sexuality through this obsession with the body as a sexualised object, in part because the culture around me often seemed to be telling me there was no other way.

Both Cook and Tom of Finland, with their pleasingly lurid exaggerations of the male and female body and sex acts, create an outré sexuality that therefore feels familiar. I know I have looked at a cock as hungrily as the woman peering into the opening thong of the beefcake pole dancer in Cook’s 1981 painting Ladies Night (Ivor Dickie).

While for the other women around her, the encounter is just a bit of a laugh, perhaps part of a ritual of a night out, it’s as if for her the rest of the world no longer exists. Never mind his personality, it’s not even the man’s face, or body that counts. Just the cock. This I had known in showers, in cruising grounds, saunas, on webcams, where the prospect of the cock in front of me would put me in a state of hyper-aroused focus. I have seen her face on so many other men too.

So I can understand why both homo and heterosoc have historically feared bisexual men as greedy, untrustworthy, half-formed. I met countless gay men who fetishized sex with us because, apparently, we were always up for anything, always focused on giving them pleasure thanks to our intense fixations on their bodies. Who cared if we often didn’t want to kiss if our hands and mouths were so good at being busy elsewhere?

This was a backhanded compliment. It was often accompanied by the accusation that we were merely cowardly, en route to full emergence as gay men just as soon as we could come to terms with it. Men I had sex with in real life or online would give patronising smiles when they found out I was from a religious background, as if to say, “you’ll be fine, dear, once they die”. These prejudices can take the form of direct attacks. When my first book, Out Of The Woods, was published, a particularly demented review in the Evening Standard described me as “weedy, needy and seedy” and (this in relation to being abused as a teenager) as a “typical switch-hitter, he wants to have it both ways.” That I could shrug off as excellent free marketing from a pathetic neurotic, but the assumptions about bisexual men tend to push us into the treacherous ambiguity of the closet.

So some perhaps assume that the perfect pricks and glorious arses of Tom of Finland and Beryl Cook make for a permanently looping obsessional film reel in the eyes, minds and desires of the perma-horny bisexual. Sure, this might have been the case at times, but by looking more deeply into their art, and from the perspective of one who has retired from all that caper, I find much of the chaos and mess of bisexuality, the taboos and titillation, and the joy.

The richness of our desire is reflected in the complex sensuality of their paint and ink. Compared to contemporary porn, Tom of Finland and Beryl Cook’s work feels naughty, subversive, cheeky. The bawdiness is such a relief from the dreary functionality of 10-minute videos on PornTube websites or earnestly politicised era of hashtag empowerment and sex positivity. I love Cook’s Anyone for a Whipping?, of brothel madame Cynthia Payne thrashing a middle-aged cross-dresser because it reminds me of an old-fashioned English wrongness, the sort of thing Tory MPs used to get up to. It’s all nudge-nudge, wink wink, how’s yer father, Black Lace singing, “having a gang bang, having a ball”.

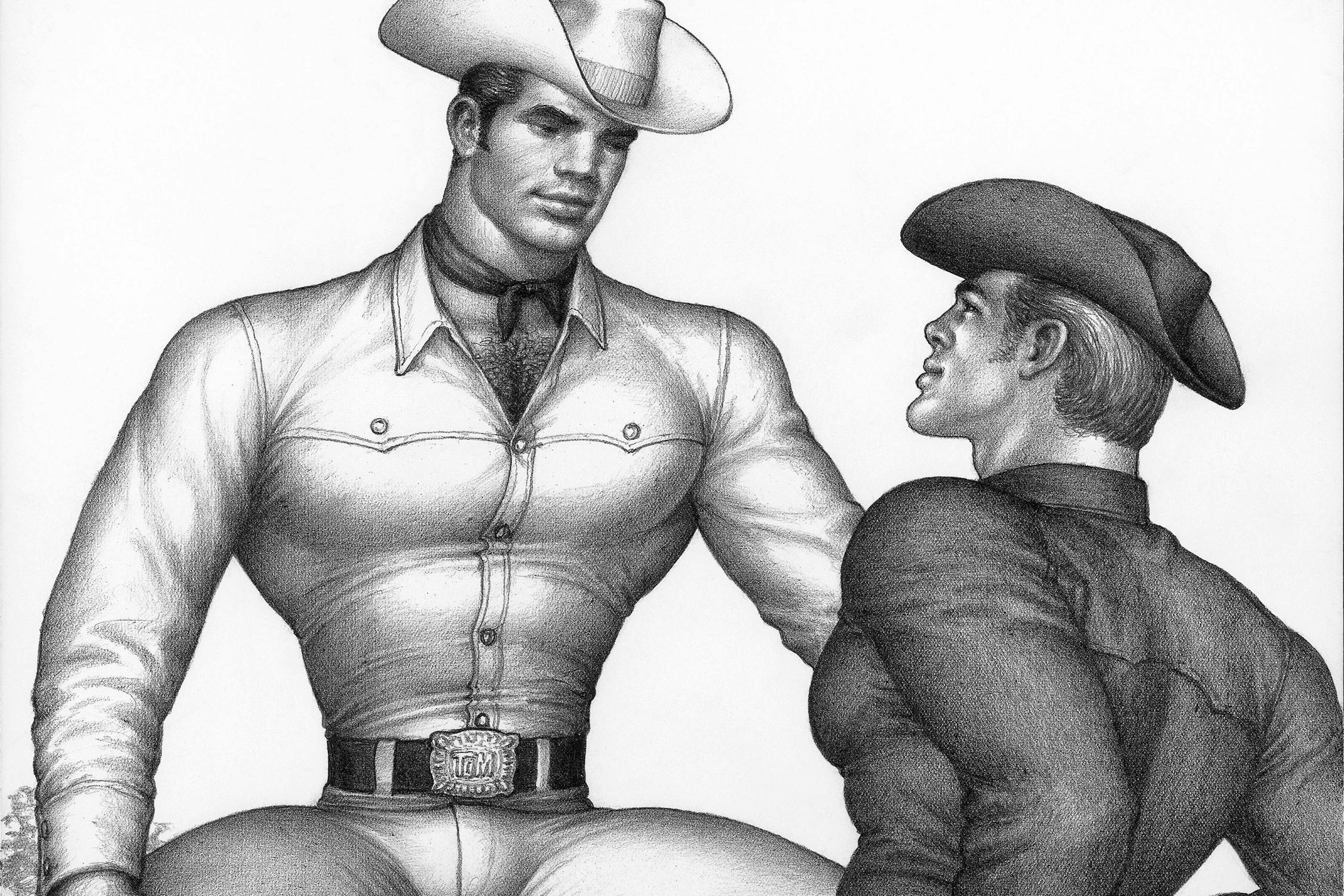

In a similar way, Tom of Finland’s work feels almost charming compared to the artlessness of contemporary mainstream idealised masculinity. Ironically enough, I prefer his-over-the top, drawn male physiques to the display of taut flesh today, probably because Tom of Finland presented a pleasurable fantasy, rather than a damaging standard to live up to. He’s arguably closer to pre-existing archetypes of queer erotica than he is to contemporary excess. When I see his images in Pictoral I think of the pages of British pre-war fitness magazine Health and Strength, which featured photographs of muscular men in tiny posing pouches alongside exercise routines and advice on how to avoid the menergy-sapping dangers of masturbation, and the problems of erectile dysfunction. By the way, this advice was dispensed by a man called ‘Standwell’.

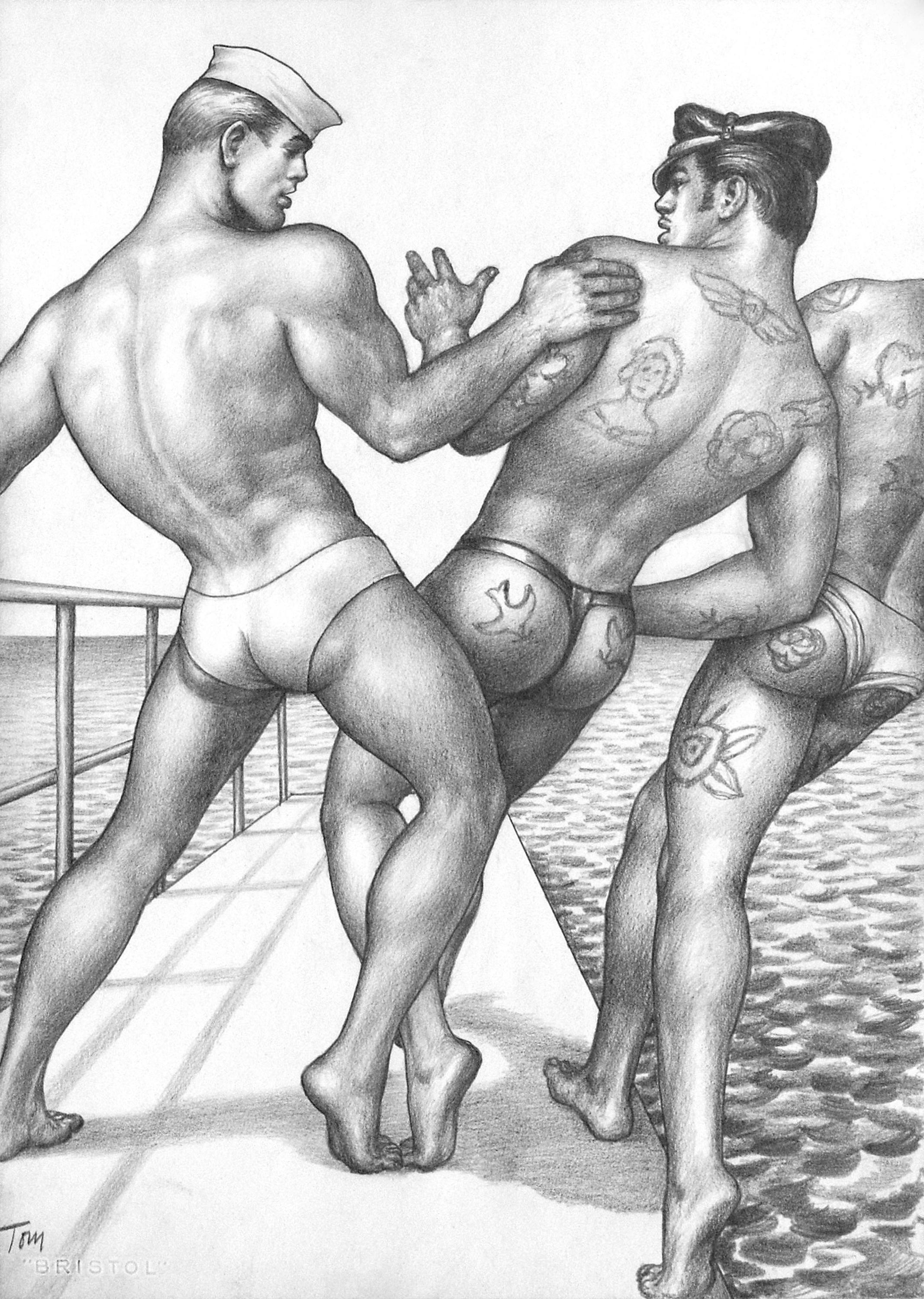

When I look at image of a sailor pushing two of his tattooed comrades into gently rippling water, I also see Swedish artist Eugène Jansson’s sublime 1907 painting Naval Bathhouse, where nude men ripple in blue as they watch the perfect form of a diver drift down towards the water.

When I look at Tom of Finland’s drawing of two men in thigh-high riding boots, sparring with long poles (not, for once, their own) I think of Montague Glover’s photographs of members of the Guards regiments of the British Army. The Guards were, during the 20th century, so notorious as being available, at a reasonable price, for men wanting “a bit of scarlet” in the Royal Parks that there were regular meetings between military and civilian authorities trying to halt the practice.

What I find interesting about these images is that where Jansson and Glover used men as their subjects who were ostensibly ‘straight’, Tom of Finland gives them a strong, queer identity. It’s as if those soldiers and sailors have been taken from their more fluid, or heterosexual states and desires and brought into the homosexual realm. They become eroticised for the queer eye, but where does that leave the men themselves?

As a bisexual man I find both Beryl Cook and Tom of Finland’s work to represent worlds into which we enter, yet often feel excluded. My sense of awkwardness around my identity contrasts with the ease with which Tom of Finland and Beryl Cook’s men and women are drawn. Cook’s depiction of the leery, easy, bawdiness of heterosexual life was one that I never felt I would be able to join. The men in them were all-too-often a physical threat. The women, I felt, would never accept my fluid sexuality. Cook’s women, in pubs or hair salons, or marching off down the street in French maid’s outfits, seem gloriously at ease in their bodies, with themselves.

They also have a comfortable intimacy in their physical presence with one another, of a sort that men find hard to have. It is doubly hard for so many bisexual men to be open about their desires with their close heterosexual male friends. In 1977’s Bangs Disco Cook of course also depicts men together in a gay club. Again, growing up as a bisexual man, these were spaces in which I never felt queer enough to be permitted.

The warm, social world depicted in Beryl Cook’s art sits adjacent to the, shall we say ‘specialised’ spaces in which the men of Tom of Finland meet, perform, suck, fist and fuck. They’re often depicted in the hinterlands where sexual encounters happen, the sorts of places familiar to bisexual men – cruising areas, cottages, woodland where men feel the rough scrape of bark against their skin, hoping that it will not mark. I like the cheek of Beryl Cook’s Sabotage, featuring a group of lady bowlers, one of whom is poking her pal on a provincial bowling green, but then wonder what the building in the background might be. A public toilet cottage perhaps, where the park sun darkens in the shade of the trees around it as men wander into the chlorine gloom within, the dripping of cisterns and taps in concert with the rasp of flies and urgent grunts and gasps.

In my early 20s, out and about in central London, I’d often leave friends in the bright warmth of the sort of straight pubs painted by Cook, and disappear into the spaces that Tom of Finland idealises – Soho’s public toilets, the then overgrown margins of Bloomsbury’s squares, the diverse wanking wall of the men’s urinals at Liverpool Street Station, the gloom that beckoned between the brick gate posts of Finsbury Park. I never met one of his leather men in them. It was always more seedy than that, more strange, marginal, conflicted. At times it was liberating, at others the cause of shame and self-destruction.

Therefore I almost envy the men that Tom of Finland drew. They are there as lust objects, sure, but are also aspirational. Their beauty is in their confidence in their sexuality. The fantasy is not just in the eroticism of what they are depicted doing, but in their idealised selfhood. There were moments in my past when in, shall we say, exhibitionistic situations, that I felt a momentary rush of the power that they hold, but it was only ever fleeting. Although in putting on leather they acquire a second skin, this is not a skin of concealment, but belonging. They are proud, defiantly who they are, even when a man is on the floor, naked, his cock trampled by a shining jackboot as both his eyes and pooper stare out at the viewer, available yet sure. This is not an entirely submissive image, either – his left hand caresses another leather-covered calf with what might almost be tenderness. This balance between the hardcore erotic and emotionally available is what as bisexual men buffeted by the expectations of society, relationships, hetero and homosoc alike struggle so hard to achieve.

So the bisexual gaze meets Beryl Cook’s genius for painting the side-eye and Tom of Finland’s direct come-ons and finds in them a familiarity, a threat, an exclusion, a temporary respite. It is a gaze that is deeply complex, fraught with pleasure, pain, reaching towards an autonomy that is all-too-often denied to us. Yet in both artists part of that liberation comes in laughter, at the smuttiness of it all – a recent Guardian headline for the review of this exhibition read “one’s trying to make you laugh, the other’s trying to make you horny”. I disagree – they’re both doing both.

These days, married to a beautiful human of the opposite gender, I for all intents and purposes ‘pass’ as straight. I don’t have to risk the abuse and harassment and barriers in life faced by those in same sex couples. Yet this is still often a difficult, lonely place in which to exist. I once saw someone say that bisexuals are the only people expected to keep sex receipts for everyone they’ve ever slept with in order to prove that they qualify in their identity. I’ve wafted a couple under your noses here, but my wallet, as stuffed as a pair of Tom of Finland’s leather trousers, will remain closed and anyway, I’ve finished shopping.

I was happy to be here today, to be out and myself, as it feels like a space in which to connect with an inner truth that, on these walls and in my mind since I bluetacked Cindy Crawford and Slash 30 years ago, is the fantasy of worlds just out of reach. And just maybe, that is OK.

Thank you.